Books are my sanctuary. They are how I learn about the world and myself. And they are where I take solace when having a bad day. So when a book fails me (and I fail to put it down), everything in my life feels askew. This happened recently with Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (also called Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis de Bernières.

Books are my sanctuary. They are how I learn about the world and myself. And they are where I take solace when having a bad day. So when a book fails me (and I fail to put it down), everything in my life feels askew. This happened recently with Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (also called Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis de Bernières.

Auspicious Beginnings

As I lay down in bed with the first few pages of this book, I was enchanted by the story of Dr. Iannis extracting a decades-old pea from a patient’s ear. It was a delightful story and so unexpected. As I drifted off to sleep, I revisited my vague, sweet memories of the movie starring Nicholas Cage and Penelope Cruz and was looking forward to more.

Maddening Monologues

When I opened the book again the next day on the bus, I was confused to be ensconced in a first-person monologue. And then it seemed to be followed by another. My recollections are inexact at this moment because I’ve tried to block the story from my mind, but I was placed directly inside the mind of Il Duce, Metaxas, and someone called (at that point) simply “The Homosexual.” The chapter titles told me who was speaking but the text failed to tell me why I cared and I struggled to find the overarching story. I kept reading because it was the only book I had with me (the argument that may some day convince me to get an e-reader), but I wasn’t happy about it.

I think if I had some understanding of World War II in Greece (and a better understanding of Mussolini), I might have gotten more out of those first-person narratives. Instead I was annoyed and felt bandied about. I was looking somewhat for the story I thought I knew (although I did not remember enough of the film to make the same mistake I had the first time I read The English Patient) or the story that enchanted me that first night, so I kept reading.

Sweet Moments of Romance

Interwoven with those first-person assaults were little gems of Pelagia and her father, the doctor. And there were adorable moments of Pelagia falling for a local boy, Mandras. They were romantic like I remember the movie being. They were also a little expected. When Pelagia admired Mandras, I felt like de Bernières was writing how he would want to be admired. Perhaps that’s a writer’s prerogative (I’ve done it), but it felt vain and made me feel more separate from the story.

When Mandras becomes inconvenient, his character becomes less interesting. I don’t take issue with Pelagia’s falling out of love with him, that seemed quite natural given their separation, but I did start to wonder why this Greek god we had been supposed to admire was suddenly shunted aside into the realm of one-dimensional characters.

Captain Corelli and Pelagia also held my interest for awhile. I kept wanting to put the book down but had just enough interest in the characters to keep me going. And, much to my relief, the monologues seemed to subside.

Choosing Titles

I’m thinking a lot about titles right now as I seek the perfect name for my novel which is due to be released later this year. I’m rubbish with titles so for a long time the book was called simply Polska. As the book neared completion I examined the themes and writing and started calling the book Murmurs of the River after Chopin’s “Murmures de la Seine” which had influenced some of the rhythm of the book, but I knew the title was weak, so now I’m looking for something that will make a reader pick my book off of a virtual shelf without betraying the content. I have pages of lists of potential words and one good candidate. UPDATE: My editor and I chose to go back to basics and call this book Polska, 1994.

What I’m saying is that I know titles are both very important and very difficult. Still, I was surprised when it felt like I didn’t meet the title character (both Corelli and the mandolin) until halfway through the book. That might not be true because I read the beginning much slower than I read the end. But to me Pelagia was the center of this book, not the mandolin.

I’ve spoiled so much that I won’t go into the ending here, but I will say that the tone and style of the book changes about halfway through. And that wasn’t just because I was skimming it while waiting for the plumber to replace our pipes. I usually try to respect a writer’s decisions as final, but in this case I will say that this large book which is trying to say so many things could have used another edit with an eye to theme. I kept reading, but I was mostly sorry I did. I should have done myself the favor of putting down the book and enjoying happy memories of the beginning.

If you are a more patient soul than I, pick up a copy of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin from Powell’s Books. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

This week I am surrounded by Romania from a thought-provoking post about

This week I am surrounded by Romania from a thought-provoking post about  I have read a lot of books about the Holocaust. Memoir and fiction, books set in World War II Europe and in the US before and after. But until reading Garden, Ashes by Danilo Kiš, it had never even occurred to me that a book could be written about Yugoslavia during the 1940s without writing directly about the war. This story of a young Catholic boy, Eduard Scham, who loses his Jewish father, Eduard, attempts to focus so directly on the personal that the historical context is nearly absent.

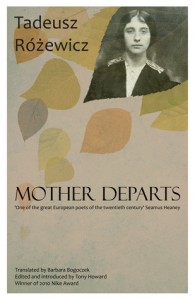

I have read a lot of books about the Holocaust. Memoir and fiction, books set in World War II Europe and in the US before and after. But until reading Garden, Ashes by Danilo Kiš, it had never even occurred to me that a book could be written about Yugoslavia during the 1940s without writing directly about the war. This story of a young Catholic boy, Eduard Scham, who loses his Jewish father, Eduard, attempts to focus so directly on the personal that the historical context is nearly absent. I was offered Barbara Bogoczek’s translation of Mother Departs by Tadeusz Różewicz for review I think because of my interest in Poland and, of late, Polish poetry. But what made me read the book this week was flipping through and seeing that mix of shapes of text on the page that belongs uniquely to hybrid forms. Since reading

I was offered Barbara Bogoczek’s translation of Mother Departs by Tadeusz Różewicz for review I think because of my interest in Poland and, of late, Polish poetry. But what made me read the book this week was flipping through and seeing that mix of shapes of text on the page that belongs uniquely to hybrid forms. Since reading