This week I am surrounded by Romania from a thought-provoking post about what people will do for a better life to a search query for my favorite tea that instead returned an album of Romanian celebration music (in French). It all started in Sun Alley, Cecilia Ştefănescu’s award-winning novel about the intoxication and torment of forbidden love.

This week I am surrounded by Romania from a thought-provoking post about what people will do for a better life to a search query for my favorite tea that instead returned an album of Romanian celebration music (in French). It all started in Sun Alley, Cecilia Ştefănescu’s award-winning novel about the intoxication and torment of forbidden love.

From the moment the young Sal first sees Emi joyously cutting apart his friends’ most prized magazines, he is enthralled with her and does everything he can to overcome the friends, parents, and life that try to keep them apart.

Central Mystery

More than a retelling of Romeo and Juliet, though, Sun Alley allows the characters to grow up. In fact, what I enjoyed most about this book was the split in time. Just as we are preparing to find out what happens when Sal and Emi prepare to run away from Sun Alley together, the time period flashes suddenly forward to an adult Sal and Emi. We discover that their attempt to flee was unsuccessful (as seemed inevitable) but we don’t learn why or how until much later.

Instead, Ştefănescu keeps the unfinished quality of their love affair in sharp focus. Though they are married to other people, they again find that they cannot bear to be apart and embark on a long, adulterous affair with all of the usual stakes. I’m not trying to be flip, but it’s obvious that husband, wife, and children cannot keep Sal and Emi apart any more than friends and parents could.

Their childhood separation is alluded to over and over as the chapters flash back and forward in time which creates a delicious tension because although we know they are (somewhat) together now, we are constantly reminded how fragile that relationship is because it has been broken before. The wonderful structure conceals as much as it reveals and I started to think about how our shifting memories betray us over time.

Other Mysteries

“He cringed in terror. He knew quite well what was on that table. It was someone. A human being, a body, a creature.” – Cecilia Ştefănescu

There is a second mystery in this book, that of a dead body young Sal finds in a basement one afternoon. It’s a truly creepy scene and made me think about how children really act versus how we like to think they act. I think this book erred on the side of how they really act, though, and it was a good lesson for me about not being squeamish about letting your characters follow their paths. I’m glad Ştefănescu didn’t take a more restrained approach to Sal’s interaction with the body, but I do wish that the body subplot was a more integrated part of the story throughout. There were echoes of it and the resolution (which I will not spoil for you) is just right, but I lost the trail sometimes as I focused on Sal and Emi’s love affair.

Significant Detail

Details show a reader where to focus. When something is important, a writer will often layer in more and more detail to signal to the reader that it’s time to really examine a scene. In the case of Sun Alley I was lost in the detail for nearly all of the first chapter. There are readers who love having every sense titillated along the way as they enter a world. I usually look for a bit more guidance and this overly detailed beginning left me grasping for understanding.

“He thought a while and then lightly touched the cockroach’s hump with his nail. It stopped, curled up and slowly moved its legs, seemingly begging to be left alive. Sal lifted his finger and sat down on the kerb next to the cockroach.” – Cecilia Ştefănescu

This is a stylistic choice and some very popular books like Atonement use the same approach. On rereading this beginning, I found that Ştefănescu does as good of a job at tying these descriptions to her overall theme as McEwan does (which is to say she does it very well), but it still drives me a little nuts.

Writing True Dialogue

One of my favorite parts of the book is a fight that Sal and Emi have at the end. I won’t quote it for you here because I don’t want to reveal too much, but writing a good, tense dialogue is something I struggle with. Here Ştefănescu lays out two characters who are standing their ground firmly and we as readers can see that there are moments when they are talking about completely different things without realizing it. So there is conflict and tension and possible resolution but the scene is so well written that I can easily believe one might never see what the other is truly saying. That’s an art and a delicate balance and Ştefănescu does it very well.

Although the ethnologist in me hoped that something about this book would come off distinctly Romanian and I’d learn more about Ştefănescu’s country of origin, I was not at all disappointed to find instead a book that will appeal to anyone who has ever experienced the joy and suffering of forbidden love.

If this review made you want to explore Sun Alley, pick up a copy from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

I finally started reading the book this week because I had 20 books left to read to meet my 2012 reading goals and I thought I could power through the 70 pages and move on to the next thing. I was so completely wrong.

I finally started reading the book this week because I had 20 books left to read to meet my 2012 reading goals and I thought I could power through the 70 pages and move on to the next thing. I was so completely wrong.

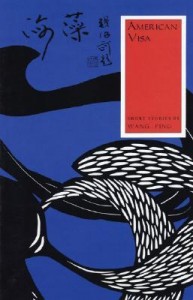

American Visa: Short Stories by Wang Ping covers locations as disparate as the Red Chinese countryside and the New York Subway. The life of her character, Seaweed, is never easy, but the author’s telling of the stories using only the sparest detail removes all trace of melodrama and lets the reader experience it for herself. Using short declarative sentences, Wang lays out the bare facts of the Cultural Revolution, spousal abuse, making it in America as an immigrant, and feeling unloved as a child.

American Visa: Short Stories by Wang Ping covers locations as disparate as the Red Chinese countryside and the New York Subway. The life of her character, Seaweed, is never easy, but the author’s telling of the stories using only the sparest detail removes all trace of melodrama and lets the reader experience it for herself. Using short declarative sentences, Wang lays out the bare facts of the Cultural Revolution, spousal abuse, making it in America as an immigrant, and feeling unloved as a child.