It feels like a natural day to reflect on silence as my husband is on a field trip with our son and I have the whole house (and garden!) to myself. It’s just me and the distant sirens on this hermitage (oh, the joys of opening the windows on a summery day). But I’ve been thinking about silence and the things we say and don’t say ever since I read Pico Iyer’s Aflame, followed quickly by The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk.

Peaceful Reflection in Aflame: Learning from Silence

Maybe I’m always thinking about silence. That’s part of the reason why I put Aflame on my Christmas, birthday, and Mother’s Day wish lists. Of course I love Pico Iyer’s work and worldview, and I’ve been re-exploring Buddhism in this time of reconsidering after I left my job. That last bit is why this book felt so necessary for me right now—the book being not just about one retreat Iyer took, but instead touching on the hundreds of retreats he’s taken throughout his life.

Maybe I’m always thinking about silence. That’s part of the reason why I put Aflame on my Christmas, birthday, and Mother’s Day wish lists. Of course I love Pico Iyer’s work and worldview, and I’ve been re-exploring Buddhism in this time of reconsidering after I left my job. That last bit is why this book felt so necessary for me right now—the book being not just about one retreat Iyer took, but instead touching on the hundreds of retreats he’s taken throughout his life.

“The new Pope [Francis] prayed, I read, not for an answer to any problem, but only for the courage to live with the unanswerable.” – Pico Iyer, Aflame

Iyer writes of how this annual ritual, coupled with one he undertakes in Japan in a different season, enriches his life. He describes that at the hermitage, “Nothing feels forbidden here because there’s no one I’m supposed to be.” A feeling I can relate to in this silent afternoon. It’s hard to make the most of it, because, as a monk relates to Iyer, “We bring [stress, acceleration, dividedness] with us… And sometimes it can be more intense here because it’s more internal.” In truth, I’ve felt myself puttering around today, looking for something to do, wondering what it even is that I want to do or even eat. I know from writing retreats, though, that this feeling passes when I give myself the time to stop worrying into it. As another monk that Iyer quotes says, “[P]eople need the silence to hear themselves.”

What made me want to write about this book, though, is the spareness with which Iyer details his experiences. It’s a stylistic choice, and one that leaves the reader open to insert their own experiences, worries, and meditations into the space. It can also feel odd at times, like when Iyer writes of a songwriter friend. He mentions some lyrics that sound vaguely familiar, but leaves off naming Leonard Cohen for quite some time. This technique effectively focuses the reader (at least one with a poor memory) on what they are discussing rather than the blam, in-the-face fame moment, which I appreciate. But the name drop still slapped me when it occurred and I found myself wondering if Iyer had argued with his editor about even including it, because the book is rich and relatable enough on its own.

Reading this book is itself a meditation. While I miss taking writing retreats (I will again, someday, when I figure out how a better balance between earning and making), just spending time leafing through this book helped me deepen my sense of peace and understanding of the world. Which helped me remember also that there is joy in engaging with it.

“The Buddha’s lesson, too, excessive renunciation is still excess.” – Pico Iyer, Aflame.

Saying the Quiet Part Out Loud in The Empusium

I have also loved Tokarczuk’s work before, though The Books of Jacob was a bit much for me. So I opened The Empusium thinking only that I was ready for whatever ride she wanted to take me on. I was not prepared for how closely this book mirrors The Magic Mountain, nor was I prepared for how effectively she was going to use a profluence of words against the characters who are speaking them.

I have also loved Tokarczuk’s work before, though The Books of Jacob was a bit much for me. So I opened The Empusium thinking only that I was ready for whatever ride she wanted to take me on. I was not prepared for how closely this book mirrors The Magic Mountain, nor was I prepared for how effectively she was going to use a profluence of words against the characters who are speaking them.

The Empusium is, in that way, the exact opposite of Aflame, because it’s only by filling in an excess of detail that Tokarczuk can show us what we’ve been failing to see all along. The book follows Mieczysław Wojnicz as he travels to a health resort to be cured of “various conditions best understood not by him but by his father.” Which, I understood from reading more of the book, was a deep shot not just at Wojnicz the elder as patriarch but at the Patriarchy in general.

This book cleverly turns the Patriarchy flat on its head in many ways, but the one I most wanted to share with you today is how Tokarczuk fills the mouths of the men around Mieczysław with the words and ideas of many great thinkers throughout history.

- “In the philosophical sense we cannot treat a woman as a comprehensive, complete subject of the kind that man is.”

- “A woman should have her rights, of course, but she should never forget that she belongs to society, which appoints the institution of the state to take care of its interests, so to but it logically, a woman, hm, hm, can be commanded by the state.”

- “Women…are incapable of creating a national organization, or even a tribal one, because by their nature they submit to those who are stronger.

Unfortunately, we live in a time when not all audiences would read these ideas as outdated. Some would, alas, celebrate the misogyny. The beauty of what Tokarczuk has done, though, is allowing people to read those characters however they choose, piling (to me) uncomfortable statement on top of uncomfortable statement and then smacking anyone who is confused on where her moral center lies with an author’s note at the end:

“All the misogynistic views on the topic of women and their place in the world are paraphrased from texts by the following authors: Augustine of Hippo, Bernard of Cluny, William S. Burroughs, Cato, Joseph Conrad, Charles Darwin…[and so on to include 30 additional fathers of knowledge]” – Olga Tokarczuk, The Empusium

There are other, subtler ways she plays with masculine and feminine roles and stereotypes in this book. There are also less subtle things involving copulating with holes in the ground. It’s a masterful and darkly funny book, one that’s direly needed in the now. If only we could get people to read it…

I’m off to hang out in the hammock with Gary Shteyngart as he skewers the 1% class… May your weekend be filled with the kinds of silence you most love.

“‘Everything will be all right in the end,’ says Cyprian, steering the car away from the precipice. ‘I fully believe that. If it’s not all right, it’s not the end.'” – Pico Iyer, Aflame

If you need a meditation or a wake-up call, pick up a copy of Aflame: Learning from Silence or The Empusium from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie bookstores in business and I receive a commission.

This polyphonic history of post-Soviet Russia is fascinating. It’s fascinating as events unfold with Navalny in Russia. It’s fascinating as the U.S. seems intent on forgetting our own attempted coup. It’s fascinating in general to remember what it was like to live through the fall of the Soviet Union and the clashes and shifts in that country in the years following. It’s also fascinating for me as someone who’s always been interested in the Eastern European parts of my heritage.

This polyphonic history of post-Soviet Russia is fascinating. It’s fascinating as events unfold with Navalny in Russia. It’s fascinating as the U.S. seems intent on forgetting our own attempted coup. It’s fascinating in general to remember what it was like to live through the fall of the Soviet Union and the clashes and shifts in that country in the years following. It’s also fascinating for me as someone who’s always been interested in the Eastern European parts of my heritage.  My Russian deep-dive may have started with an attempt to finally get this tome off my to-read shelf before the opening the stack of books awaiting me for my birthday. It might also have started because I was remembering

My Russian deep-dive may have started with an attempt to finally get this tome off my to-read shelf before the opening the stack of books awaiting me for my birthday. It might also have started because I was remembering  I was thrilled when I found this gem in a local Little Free Library one day this past fall, because Ozeki and Abani are two of my very favorite writers. I was also excited to delve into the very personal stories in the book as I work to learn more about individual experiences of race.

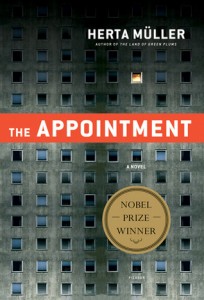

I was thrilled when I found this gem in a local Little Free Library one day this past fall, because Ozeki and Abani are two of my very favorite writers. I was also excited to delve into the very personal stories in the book as I work to learn more about individual experiences of race.  This book is actually fiction based on stories from someone who experienced the same deportation to the gulag. I’ve lost the book somewhere (or given it away, it was oh so very depressing), so I cannot treat you to any of Müller’s sentences or the fantastic imagery she imbues into this bleak, bleak experience, but this book is one of the most beautifully written things I’ve read in a very long while and it will make almost any pandemic experience seem cheery.

This book is actually fiction based on stories from someone who experienced the same deportation to the gulag. I’ve lost the book somewhere (or given it away, it was oh so very depressing), so I cannot treat you to any of Müller’s sentences or the fantastic imagery she imbues into this bleak, bleak experience, but this book is one of the most beautifully written things I’ve read in a very long while and it will make almost any pandemic experience seem cheery.  Now we’re snowed in for the long weekend, and after finally finishing the Alexievich book (so good, so long, such small print), I decided to treat myself to Thomas Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation. I’m not very far along, but already it’s a bit like

Now we’re snowed in for the long weekend, and after finally finishing the Alexievich book (so good, so long, such small print), I decided to treat myself to Thomas Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation. I’m not very far along, but already it’s a bit like  Bless the books that find you at just the right time in your life. I first started hearing about Olga Tokarczuk and House of Day, House of Night this past fall, received it for Christmas, and started reading it the weekend after my grandfather (

Bless the books that find you at just the right time in your life. I first started hearing about Olga Tokarczuk and House of Day, House of Night this past fall, received it for Christmas, and started reading it the weekend after my grandfather ( This was actually the second time I tried to read this book. I took it on a week-long beach getaway for my husband’s and my first anniversary. Then it sat on my bedside table for a couple of years and I managed to read 100 pages before tucking it away. So when I knew I’d be home for a prolonged maternity leave, I dug it out again. I knew from reading

This was actually the second time I tried to read this book. I took it on a week-long beach getaway for my husband’s and my first anniversary. Then it sat on my bedside table for a couple of years and I managed to read 100 pages before tucking it away. So when I knew I’d be home for a prolonged maternity leave, I dug it out again. I knew from reading  I picked this book up at the local Little Free Library because I’ve enjoyed many of Julian Barnes’s novels. I thought it would be a quiet, meditative, well-written novel that would reach into my subconscious and teach me things about writing. I did not think it would be about Flaubert’s parrot. Literally. Well, actually, two parrots (because only one could have really been Flaubert’s), stuffed.

I picked this book up at the local Little Free Library because I’ve enjoyed many of Julian Barnes’s novels. I thought it would be a quiet, meditative, well-written novel that would reach into my subconscious and teach me things about writing. I did not think it would be about Flaubert’s parrot. Literally. Well, actually, two parrots (because only one could have really been Flaubert’s), stuffed. Konrad is one of those obscure Eastern European writers I read in grad school. And loved. I read

Konrad is one of those obscure Eastern European writers I read in grad school. And loved. I read  When I woke this morning, I didn’t want to pick up The Appointment by Herta Müller even though I only had a few pages left to read. I successfully avoided the book all day yesterday, too. But not for the reasons you might think. I set the book aside because it was so good, so cleanly and smartly written, that I didn’t want it to end.

When I woke this morning, I didn’t want to pick up The Appointment by Herta Müller even though I only had a few pages left to read. I successfully avoided the book all day yesterday, too. But not for the reasons you might think. I set the book aside because it was so good, so cleanly and smartly written, that I didn’t want it to end.