I started reading Aureole by Carole Maso because Goodreads told me that Gwendolyn Jerris wanted to read it and I needed the kind of book that Gwen loves—lyrical literature like Inner China that falls somewhere between poetry and prose. It’s a type of writing that echoes that of our shared advisor, Micheline Marcom, and one I think we both aspire to in our own way. I started reading this book because I needed to get lost in language—to see again what some of its outer limits are.

I started reading Aureole by Carole Maso because Goodreads told me that Gwendolyn Jerris wanted to read it and I needed the kind of book that Gwen loves—lyrical literature like Inner China that falls somewhere between poetry and prose. It’s a type of writing that echoes that of our shared advisor, Micheline Marcom, and one I think we both aspire to in our own way. I started reading this book because I needed to get lost in language—to see again what some of its outer limits are.What I didn’t realize until I opened the book and started reading the introduction was how very perfect this book would be for stretching my language and my thinking. To start with, it turns out that Maso is, like I, a prose writer writing poetry. Longtime readers of this blog will have seen me fall in love with all kinds of writers who dance along that line (most notably Anne Michaels and Michael Ondaatje). But when Maso started describing her process for writing this book—for the way she was deliberately reinventing her language—I was hooked. She writes “If I felt I was doing something I already knew how to do well, the rule was to start again.”

Part of my struggle is that I’ve been doing a lot of blogging lately. And I don’t mean for this blog. At work, I’m writing about content marketing and other forms of digital marketing where the very best thing I can do for the audience is write simply and clearly as I try to demystify aspects of the topic. What that’s left for this writer, though, is a large hole in my creativity where I want to be mysterious. I want to be oblique. I want to stretch pull tease and twist language until it does my bidding and my readers can learn about how to reinvent their worlds along with their words rather than following expected paths to get measurable results.

Finding Sense in Nonsense

“When they are French, which they often are, especially in bed they say dérangement. When they are French, and this is Paris, which it often is—so beautiful, so light-dappled, such light—the window opening up onto everything, everything: the tree-lined boulevard, the stars, the Tour Eiffel, she says, it’s like a cliché, only beautiful: croissant, vin rouge, fromage, French poodles, polka dots. When they are French.” – Carole Maso

Actually, the passage above is hardly nonsense, at least not in a Steinian sort of way (though I know Maso was reading Stein when she wrote this). But there is a certain amount of arbitrariness and randomness to the connection of the thoughts. When they are French? Usually Frenchness is more of a permanent state than that. This allowance that it’s an identity the two characters can put on or take off is playful and perhaps something they put on when they are in France. As this story evolves, “When they are French” also starts to mean when they are lovers or in bed. I absolutely adore the openness of this and the fact that some of the meaning I’ve just imparted comes from my head and that if you read this story, you might have an entirely different (and equally valid) meaning.

That openness of meaning is so much what I crave reading and also writing. A work that only achieves its full meaning through interaction with a reader just seems like magic to me. And although I bring my own feelings and experiences into a reading of Madame Bovary, you and I are much less likely to be able to build castles of our own interpretations of it because the narrative and language are much more conventional.

Sound

“A dream of sucking, akimbo.” – Maso

Now would probably be a good time to mention that this book is mostly comprised of erotic adventures both hetero- and homosexual. In case erotica isn’t your thing. In many places Maso exploits the softer vowel sounds so well as the crescendo of each act builds that I didn’t even see what she was doing until she interposed a different, harder sound. At some point I’d really like to re-read this book aloud just to feel her mastery of sound.

Rhythm of Language

“And she opens her hand, her life to him: a blur of wings.

And desperately.

And desperately then.” – Maso

Another thing that really makes me want to read this book aloud is the way that Maso uses the rhythm of the words. Imagine after reading an entire chapter of foreplay and play and allusions to the act of sex, reaching this peak…

You Can’t Push All the Time

All of this fabulous word play and invention of syntax and crazy sensuous juxtaposition so pushed my thinking of what words can do that when I reached a line that read “threshold of all possibility,” the mundanity of those words only highlighted how wonderful the rest of the book is. What this means for me and my writing is that if I’m going to push the limits, I’m going to have to really go for it, because the moments that I flinch or get lazy will be obvious to the careful reader. And worse, they will disappoint me if I catch myself doing it.

The Next Journey

A completely unexpected moment in this book is when Maso references India. I’m actually leaving for India in just over a week and suddenly it’s everywhere, including in A Mapmaker’s Dream, another book I read this weekend.

That sounds like a complete and total non sequitur, but I had to find some way to drop in the fact that my blogging might be a bit sporadic in October. I’ve bought all of these books:

(Two of which I’ve since read) and I plan to pack as many of them in my luggage as I can and to write when I can. Maso described a character’s “ink-stained hands (the measure of her day)” and I plan to get some of that in as well. Maybe I can find my own language in the interstices of poetry and prose. I’m sure as hell going to try.

If you want to open up the boundaries of the way you use language, pick up a copy of Aureole from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

It had been a very long time since I read Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. I own (and proudly wear) the t-shirt from Out of Print Tees, but I was starting to get embarrassed when people made soma references when they saw me in it and I had no idea what they were talking about. So this week, in honor of Banned Books Week, I reread this classic novel and what I found shocked, impressed, amazed, and disappointed me. But I’m not sorry I read it.

It had been a very long time since I read Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. I own (and proudly wear) the t-shirt from Out of Print Tees, but I was starting to get embarrassed when people made soma references when they saw me in it and I had no idea what they were talking about. So this week, in honor of Banned Books Week, I reread this classic novel and what I found shocked, impressed, amazed, and disappointed me. But I’m not sorry I read it. Who will we become? Is the longing for something greater in life something we should chase or should we be happy with what we have? When farm boy Orno Tarcher meets the worldly Marshall Emerson on Orno’s first day at Columbia in For Kings and Planets by Ethan Canin, these are the questions that are set in motion. And if the book had lived up to that struggle, I would have been thrilled.

Who will we become? Is the longing for something greater in life something we should chase or should we be happy with what we have? When farm boy Orno Tarcher meets the worldly Marshall Emerson on Orno’s first day at Columbia in For Kings and Planets by Ethan Canin, these are the questions that are set in motion. And if the book had lived up to that struggle, I would have been thrilled. I started reading The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium & Discovery by Amitav Ghosh because I’ll be traveling to India in just over a month. The book had been in my to-read pile for ages and I’d heard good things about it, I just wasn’t ready to read it… until now. And what I found in those pages made me glad I waited to read it, because if I had read this book at any other time, I would have missed what became the central lesson of the book for me: thinking beyond the expected.

I started reading The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium & Discovery by Amitav Ghosh because I’ll be traveling to India in just over a month. The book had been in my to-read pile for ages and I’d heard good things about it, I just wasn’t ready to read it… until now. And what I found in those pages made me glad I waited to read it, because if I had read this book at any other time, I would have missed what became the central lesson of the book for me: thinking beyond the expected. I picked up Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit on a night when I was headed to a gathering of female writers (a group that will not be named). During dinner before the event, Ann Hedreen and I discussed what we really thought of this group. I was wrestling with the fact that the event had to be secret. That the organizers felt they had to exclude men. And that they had named their group after a remark by someone they would consider part of the patriarchy. It all felt so reactive.

I picked up Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit on a night when I was headed to a gathering of female writers (a group that will not be named). During dinner before the event, Ann Hedreen and I discussed what we really thought of this group. I was wrestling with the fact that the event had to be secret. That the organizers felt they had to exclude men. And that they had named their group after a remark by someone they would consider part of the patriarchy. It all felt so reactive. The next book I picked up, When She Named Fire is a collection of poems by women. I have to admit I haven’t gotten very far into the book yet because I was so floored by

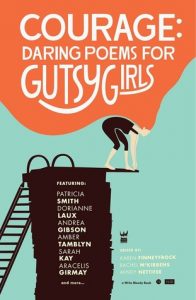

The next book I picked up, When She Named Fire is a collection of poems by women. I have to admit I haven’t gotten very far into the book yet because I was so floored by  Courage: Daring Poems for Gutsy Girls was co-edited by

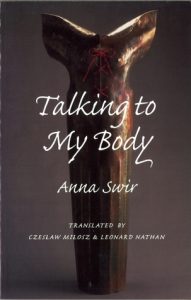

Courage: Daring Poems for Gutsy Girls was co-edited by  The irony of Talking to My Body is that I found author Anna Swir through a collection anthologized by Czesław Miłosz who at every turn celebrated her feminism but in the most misogynistic tone. I can’t really explain and I think it was well intentioned and also cultural. Regardless, after reading one or two of her poems, I had to have more.

The irony of Talking to My Body is that I found author Anna Swir through a collection anthologized by Czesław Miłosz who at every turn celebrated her feminism but in the most misogynistic tone. I can’t really explain and I think it was well intentioned and also cultural. Regardless, after reading one or two of her poems, I had to have more.