I’m still trying to figure out where I fit in the world, reconceptualizing my career and the way I spend my time. Naturally, I’m turning to books, but I’ve also been slowing down, paying attention to moments and returning to old favorites. Recently, that brought me to The Bicycle Book by Bella Bathurst, but I didn’t realize what I needed most about that book until a visit to the Ai, Rebel show at the Seattle Art Museum yesterday, and now I can’t stop thinking about all the ways connecting to the tangible is the best healing and the best path forward I have.

The Bicycle Book by Bella Bathurst

I first fell in love with Bathurst’s writing when I read an excerpt of The Lighthouse Stevensons, and I bought The Bicycle Book because I love the way Bathurst allows her curiosity to guide her exploration of whatever she’s writing about. And because I dream of fixing up my mom’s old Gitane someday and riding down to the park with the wind in my hair. It’s a project I started last summer, but I stalled at the “I really want to repaint this, but to repaint if I have to take it apart… and then what?” stage. The bicycle is functional, but not as beautiful as when my mom rode it around Seattle before I was born or when my dad had his and my bikes repainted in high school in any color I wanted. Aqua is the color of a father’s love.

I first fell in love with Bathurst’s writing when I read an excerpt of The Lighthouse Stevensons, and I bought The Bicycle Book because I love the way Bathurst allows her curiosity to guide her exploration of whatever she’s writing about. And because I dream of fixing up my mom’s old Gitane someday and riding down to the park with the wind in my hair. It’s a project I started last summer, but I stalled at the “I really want to repaint this, but to repaint if I have to take it apart… and then what?” stage. The bicycle is functional, but not as beautiful as when my mom rode it around Seattle before I was born or when my dad had his and my bikes repainted in high school in any color I wanted. Aqua is the color of a father’s love.

Much to my delight, The Bicycle Book starts with Bathurst working with a craftsman to build her own bike from steel. I’ve always wanted to weld, so my envy was pure, but also there was so much to be learned (for writer and reader) in this process of hands-on creation. I loved that section of the book most, although I spent most of the next week telling my husband fun facts about everything from the various subcultures of bike messenger in cities across England to how bicycles democratized transit in most of the world (and how England lost out).

Ai Weiwei Makes Tangible

No segue here because the book faded from my mind for a few weeks until I saw at the SAM show what Ai had done with bicycles. In the picture above, you’ll see the pile of dismantled and cut apart bicycle parts that lines a whole wall in the museum. Below is “Forever Bicycles,” a structure built from the most common type of bicycle in China (the pile of parts is in the background here).

The type of bicycle is important because bicycles were also a democratizing element in China, giving people the power to travel farther distances. There’s a more complicated message involving China’s recent history, but I got sucked into the way Ai is playing with the bicycle as material—both as a material object and the materiality of its component parts.

As a recovering sculptor, I was obsessed.

I held that feeling of the delight of play with me until I walked into the next room of the exhibit—a room whose ceiling is filled with a snake made of backpacks. “Snake Ceiling” seems playful, but it is also deadly serious, recalling the thousands of children who died in substandardly built schools during the 2008 earthquake. It was then that I felt a deep kinship with Ai Weiwei. You see, I am filled with generative energy. Using that to build, make, or create things is the best contribution I have to the world. It also keeps me sane. I once created a painting pierced with thousands of french knots representing the people who died of AIDS in Africa in because I wanted to feel each life for a moment.

While there are interesting things he does (including a wall-size depiction of the Mueller report in Lego overseen by a marble surveillance camera), the pieces in the show I returned to were the ones where I could feel the tangibility of material objects.

For instance, the stack of stools above was endlessly fascinating to me. I loved the way they all looked the same, but they aren’t. You can see from the supporting structure between the legs of each stool that some carpenters used a triangle and others used a key. One even created something that looks like a star (see below). The gentle differences in each of these handmade objects spoke to me and I could imagine the satisfaction of running my hands over the wood in building one. My dad was a carpenter a long time ago and I wonder if I inherited this love of making from him or if connecting with tangible objects is something all humans need.

I took that feeling of tangibility with me on the rest of the field trip (it was the last Friday date my husband and I will have alone for awhile because school lets out next week) as we walked into Pike Place Market. There, the bricks in the street are being relaid.

We didn’t get to see any workers, but I thought about the people behind these processes. It could be such a monotonous job, but I hope they find pleasure in building something that is so foundational, just as I felt pride this week when I was able to help my husband mud the drywall in the artist studio he’s building out back. I am not good at it, but I can imagine what it would feel like to do the same thing over and over with my hands until my work is nearly invisible.

The last stop on our field trip was to visit a friend who had made—with her hands—a pair of glasses for me.

The Changing World

I won’t go into politics, because what even can I say, but the world is changing around us in a lot of ways. In my neighborhood, that means that many old homes are being torn down. It’s a good thing because we need the density, but it’s jarring because I’ve lived here for nearly 28 years. On our way home from the bus we walked past this house with the telltale temporary electric pole out front:

You can see the roof is in poor repair, something that was true for at least the last couple of years. And we wondered about the people who’d lived there, likely for a long time, and if they’d gotten priced out because it’s expensive even to have repairs done here. I won’t remember this house forever, just as I have forgotten many of the houses nearby that have been torn down in the past few years. And the change is long overdue (which makes it harder because it’s happening all at once). But it reminded me of these bricks from the Ai Weiwei exhibit:

The bricks are from old (probably ancient) homes in a hutong, the old-style alleys in Chinese cities. I’ve been to the Beijing hutong and the layers of history felt special. I can also imagine that the space could be more efficiently used, if efficiency is the goal. What I loved about this piece is the commemoration of the material, and through that, the home that once stood and the lives lived therein.

Maybe it’s because I work in digital marketing, maybe it’s because I’m a little lost right now, but these reminders of the pleasures of engaging with the material world feel deeply important. Having just wrapped the best version of my novel, Naked Driving to the Witches’ Graveyard, that I can complete on my own, it’s a great time to find new things to do with my generative energy. To figure out what I want to change and how to commemorate what once was.

If you’re interested in exploring your relationship with the tangible, I recommend The Bicycle Book and Ingrained: two books that touch on what it is to make something with your own hands. Buy them from Bookshop.org and I get a commission.

This is the book I’ve most recommended on Twitter threads this year because reading The Thirty Names of Night was such an immersive experience. This gorgeous book slides lyrically between locations (Syria, New York and Michigan), time periods, and genders as it explores themes of identity and belonging as a trans boy seeks answers about the fire that killed his mother and about a Syrian artist who disappeared. Joukhadar’s language is stunningly poetic, the characters are rich and compelling, and the action of the story is well-paced. I was a little hesitant about finishing this book because I’d loved it so much that I wasn’t sure that the ending could live up to the rest of the book. Reader, it did. If you want to get lost in a beautiful book, The Thirty Names of Night is my top recommendation for the year.

This is the book I’ve most recommended on Twitter threads this year because reading The Thirty Names of Night was such an immersive experience. This gorgeous book slides lyrically between locations (Syria, New York and Michigan), time periods, and genders as it explores themes of identity and belonging as a trans boy seeks answers about the fire that killed his mother and about a Syrian artist who disappeared. Joukhadar’s language is stunningly poetic, the characters are rich and compelling, and the action of the story is well-paced. I was a little hesitant about finishing this book because I’d loved it so much that I wasn’t sure that the ending could live up to the rest of the book. Reader, it did. If you want to get lost in a beautiful book, The Thirty Names of Night is my top recommendation for the year. My six-year-old son also loves getting lost in a good book. And while we enjoyed Beyond the Bright Sea by Lauren Wolk and the Vanderbeekers series by Karina Yan Glaser very much, Where the Mountain Meets the Moon is the perfect book for him right now, which makes it one of the most enjoyable books for me, too, because (when he isn’t bouncing back and forth on the bed) he’ll lean in close to me and put his hand across my wrist as I hold the book, an intimacy that’s already becoming rare.

My six-year-old son also loves getting lost in a good book. And while we enjoyed Beyond the Bright Sea by Lauren Wolk and the Vanderbeekers series by Karina Yan Glaser very much, Where the Mountain Meets the Moon is the perfect book for him right now, which makes it one of the most enjoyable books for me, too, because (when he isn’t bouncing back and forth on the bed) he’ll lean in close to me and put his hand across my wrist as I hold the book, an intimacy that’s already becoming rare. My own interests in Asia tend more toward Japan and Zen Buddhism and I am a longtime fan of

My own interests in Asia tend more toward Japan and Zen Buddhism and I am a longtime fan of  I don’t always read the right books at the right times (or do I?), having read

I don’t always read the right books at the right times (or do I?), having read  I already wrote about

I already wrote about  The idea that a book is brought to life by its reader is not new. A writer pours all of the details and plot that they can into a work and then the reader comes along and makes it their own by keying into the things that matter to them and ignoring the things that don’t. This conversation and co-creation between writer and reader feels like magic when we allow ourselves to surrender to it. Yesterday, though, Ruth Ozeki took me beyond that magic to make me feel as though A Tale for the Time Being was not only written for me, but was being written for me as I read it. I wanted to go back and re-read it immediately to see if it changed. I also wanted to have you read it immediately to see if it was a completely different book for you. It probably isn’t (not really) but it’s very much worth a read either way. I’m going to delve into where the magic came from for me. Just

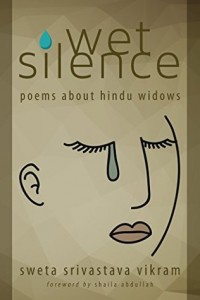

The idea that a book is brought to life by its reader is not new. A writer pours all of the details and plot that they can into a work and then the reader comes along and makes it their own by keying into the things that matter to them and ignoring the things that don’t. This conversation and co-creation between writer and reader feels like magic when we allow ourselves to surrender to it. Yesterday, though, Ruth Ozeki took me beyond that magic to make me feel as though A Tale for the Time Being was not only written for me, but was being written for me as I read it. I wanted to go back and re-read it immediately to see if it changed. I also wanted to have you read it immediately to see if it was a completely different book for you. It probably isn’t (not really) but it’s very much worth a read either way. I’m going to delve into where the magic came from for me. Just  How many ways can you write about widowhood? In Wet Silence: Poems about Hindu Widows, Sweta Srivastava Vikram explores every nuance of what life is like for a Hindu widow in India. It’s as much a human exploration as a cultural one as Vikram delves into the aftermath of the complex relationships that underlie arranged marriages. Some of the widows in this collection are devastated that their beloved husbands have passed. Others rejoice in their new freedom from abuse and adultery. Still others face new complications in their relationships with the families to which they have now become burdensome.

How many ways can you write about widowhood? In Wet Silence: Poems about Hindu Widows, Sweta Srivastava Vikram explores every nuance of what life is like for a Hindu widow in India. It’s as much a human exploration as a cultural one as Vikram delves into the aftermath of the complex relationships that underlie arranged marriages. Some of the widows in this collection are devastated that their beloved husbands have passed. Others rejoice in their new freedom from abuse and adultery. Still others face new complications in their relationships with the families to which they have now become burdensome. One of the things I was most afraid of in coming to India was replicating the colonial experience. This frightened me because I despise the exploitation of other peoples and cultures and I thought with my oh-so-white skin and complete lack of skill with local languages and norms that I could not avoid being seen as one of those colonizers who expects to be treated as more and better. It also frightened me because I thought I might grow to like it.

One of the things I was most afraid of in coming to India was replicating the colonial experience. This frightened me because I despise the exploitation of other peoples and cultures and I thought with my oh-so-white skin and complete lack of skill with local languages and norms that I could not avoid being seen as one of those colonizers who expects to be treated as more and better. It also frightened me because I thought I might grow to like it.