How many times in life do we really get to devote ourselves to tomes anymore? One of the projects I’ve been working on as I prepare to have my first child is getting through my to-read shelf, and, not surprisingly, some of the thickest hardbacks are the very last ones I’m getting to. That includes The Selected Short Stories of Edith Wharton (390 pages) and a collection of five novels by Henry James (Daisy Miller, Washington Square, The Portrait of a Lady, The Bostonians, and The Aspern Papers) (892 pages). Admittedly, I’m still working on the James collection, but after facing a truly embarrassing confusion between the two writers, I knew I had to write about it here.

How many times in life do we really get to devote ourselves to tomes anymore? One of the projects I’ve been working on as I prepare to have my first child is getting through my to-read shelf, and, not surprisingly, some of the thickest hardbacks are the very last ones I’m getting to. That includes The Selected Short Stories of Edith Wharton (390 pages) and a collection of five novels by Henry James (Daisy Miller, Washington Square, The Portrait of a Lady, The Bostonians, and The Aspern Papers) (892 pages). Admittedly, I’m still working on the James collection, but after facing a truly embarrassing confusion between the two writers, I knew I had to write about it here.

Biographical Comparisons

Both transatlantic writers writing about a certain social class in the northeastern US and in England, I was a little surprised to learn (though I shouldn’t have been) that James (1843-1916) and Wharton (1862-1937) knew each other and that James was a mentor of sorts to Wharton. Both were American and spent considerable time abroad although I would have sworn that James was British. Their writing shares a similar sensibility cultivated by a social class where there are a lot of tacit rules to be followed and this gives the work of both writers a lot of subtext.

The Portrait of a Lady vs. The Age of Innocence

Was that biographical snippet included here just to absolve myself of the embarrassment I’m still feeling over conflating the two writers? Maybe. What happened was that late one night I started reading The Portrait of a Lady and, having watched more film adaptations of the work of Wharton and James than there could ever be books, I assigned Winona Ryder to the character of Isabel Archer. I was a little confused that the story was taking place on the wrong continent (in England) and eventually started to get annoyed that the introduction was so very long and became impatient to see the character of Countess Olenska.

Was that biographical snippet included here just to absolve myself of the embarrassment I’m still feeling over conflating the two writers? Maybe. What happened was that late one night I started reading The Portrait of a Lady and, having watched more film adaptations of the work of Wharton and James than there could ever be books, I assigned Winona Ryder to the character of Isabel Archer. I was a little confused that the story was taking place on the wrong continent (in England) and eventually started to get annoyed that the introduction was so very long and became impatient to see the character of Countess Olenska.

I had completely conflated The Portrait of a Lady and The Age of Innocence.

My excuse (besides the fact that I’m sometimes a very poor reader) is that I strongly remember Ryder saying “Archer” a lot in the film (which makes sense because it’s her husband Newland’s last name). But it’s a pretty poor excuse considering I actually have read The Age of Innocence (though it’s been nearly a decade).

Not surprisingly, my relationship with The Portrait of a Lady changed a bit once I started reading it for itself. The book still feels overly long (I’m still reading it), although it’s a relief to read for what is happening on the page rather than what I think will happen. I can’t quite place Nicole Kidman in the book (that’s one adaptation I actually haven’t seen), and maybe that’s for the best.

I haven’t completely learned my lesson, though. I “watched” the miniseries for The Buccaneers this weekend while needlepointing a stocking for my son. God help us all if I ever pick that book up and try to remember if I’ve read it 🙂

Roman Fever

If I were to write a dissertation on James and Wharton, I’d no doubt find countless similarities (and differences) in their work. What struck me most, though, in reading these books so closely together is when they both brought up Roman Fever. I’d never heard of this curious thing before, but it seems to have been a fear that tourists had of Rome and particularly the area near the Colosseum that could prove deadly.

James wrote about the phenomenon in Daisy Miller, but Wharton’s treatment of it in “Roman Fever” is even more interesting where the fever has multiple meanings. The story really is quite wicked (in the most wonderful ways) and merits a re-read when I’m finally done with all these Jamesian novels.

Scary Stories

Both Wharton and James wrote ghost stories, they lived in a time where mediumship and the supernatural were part of high society. James is of course famous for The Turn of the Screw which I have not read but I’ve seen at least one film of. Wharton wrote enough ghostly short stories to devote an entire collection to them and while reading The Selected Stories I have to say that those ghost stories were still some of my favorites. “Mr. Jones” in particular chills me every time.

My Real Love

I’m probably always going to be team Wharton. Although both writers carefully observed the manners of their time, there’s something warmer and perhaps more human about the way Wharton portrays her characters. I believe she actually has sympathy for them, whereas I don’t think James always does.

It’s funny, I actually wrote about Wharton in my graduate school application essay because I so admired her work. I thought in my reading of all of this contemporary fiction since that I’d moved on from my somewhat archaic tastes, but in re-reading Wharton I found I still love and relate to her work whereas reading James feels more to me like wandering through a show of John Singer Sargent portraits—there’s beauty and I can relate to the pictures a little, but the characters and their time seem so far away.

I’m officially on maternity leave right now and it’s about 90 degrees in Seattle, so while I have loads of time (at least until the little one decides he’s ready), I can’t really go outside and no excuse not to read. I might actually finish this James collection. Although I’m not sure I’ll make it through that Peter Nadas book I’ve been looking forward to (1100+pages)…

If this review made you want to read turn of the last century literature, pick up a copy of the Henry James collection or The Selected Short Stories of Edith Wharton from Powell’s Books. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

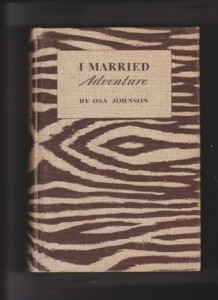

When I pulled I Married Adventure with its rough, zebra-printed cover from my rapidly-thinning to-read shelf this week, I did it because I remember my dad loving the book. I remember how he’d buy copies and sell them along with his other Africana at gun shows. I remembered entering and re-entering that book into his sales database back when Lotus 1-2-3 was a thing.

When I pulled I Married Adventure with its rough, zebra-printed cover from my rapidly-thinning to-read shelf this week, I did it because I remember my dad loving the book. I remember how he’d buy copies and sell them along with his other Africana at gun shows. I remembered entering and re-entering that book into his sales database back when Lotus 1-2-3 was a thing.

I have a confession to make. I’m only halfway through The Incredible Sestina Anthology so I really shouldn’t be reviewing it here yet, but my brain is so wrapped up in the book and the form that I wanted to share my feelings about it now both so I don’t lose the threads of what’s so exciting and so I can delve deeper into understanding the nature of that excitement. Since it’s a book of poetry, let’s bend the rules a little today, shall we? At least I know the plot won’t shift radically when I turn the next page.

I have a confession to make. I’m only halfway through The Incredible Sestina Anthology so I really shouldn’t be reviewing it here yet, but my brain is so wrapped up in the book and the form that I wanted to share my feelings about it now both so I don’t lose the threads of what’s so exciting and so I can delve deeper into understanding the nature of that excitement. Since it’s a book of poetry, let’s bend the rules a little today, shall we? At least I know the plot won’t shift radically when I turn the next page.

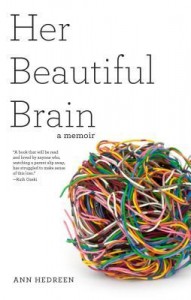

Alzheimer’s is in the news again this week with the death of beloved novelist Terry Pratchett. I say again, but it seems as though Alzheimer’s is never really out of the news. And while my own life has (thankfully) not been touched by this terrible disease, reading Her Beautiful Brain, a memoir of a daughter’s struggle with her mother’s early onset Alzheimer’s by my friend Ann Hedreen, I see how personal and how consuming the disease is both for those who are suffering from it and for each and every one of their family members.

Alzheimer’s is in the news again this week with the death of beloved novelist Terry Pratchett. I say again, but it seems as though Alzheimer’s is never really out of the news. And while my own life has (thankfully) not been touched by this terrible disease, reading Her Beautiful Brain, a memoir of a daughter’s struggle with her mother’s early onset Alzheimer’s by my friend Ann Hedreen, I see how personal and how consuming the disease is both for those who are suffering from it and for each and every one of their family members.