When a dear friend sent me a copy of Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, he said it was because I had a son. I don’t think I would have read the book if I’d understood it was about race in American society. But that skirting of uncomfortable topics is exactly why I needed to read this book. It’s why I think everyone should read this book.

When a dear friend sent me a copy of Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, he said it was because I had a son. I don’t think I would have read the book if I’d understood it was about race in American society. But that skirting of uncomfortable topics is exactly why I needed to read this book. It’s why I think everyone should read this book.

The Art of Persuasion

Because I’m white and because I (like everyone else) have no choice as to what race I am, I’ve often felt impugned by conversations about racism. I grew up in a very white town, but I’ve always had friends of all colors. I was pretty sure I’m not racist and so, while I know we are not at all post-racial, I haven’t really found a way to engage in the conversation about racism. So when I realized that this book was about being black in America, I was prepared to feel attacked once again for things that “aren’t my fault.”

Coates schooled me good. And he did it in two really effective ways.

Owning Your Own Experience

In reading Coates address responsibility, I began to understand the burden on the opposite side of my privilege:

“You are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Indeed, you must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to you. And you must be responsible for the bodies of the powerful—the policeman who cracks you with a nightstick will quickly find his excuse in your furtive movements. And this is not reducible to just you—the women around you must be responsible for their bodies in a way that you will never know. You have to make your peace with the chaos, but you cannot lie.” – Ta-Nehisi Coates

I realized the struggle African Americans are speaking of and experiencing isn’t about me at all. Sure, the actions I take have an effect on the world and I should do the very best I can to look beyond skin color, but I need to stop putting myself at the center of someone else’s suffering. The voice saying “this is wrong” needs to be heard. And saying “this is wrong” is not the same as saying “this is your fault.”

Reinforcing the Humanness of the Struggle

We’ve all read about slavery in school. Slavery was bad. We’ve read about racism. Racism is bad. There are some icons we remember from our history books and bandy about in conversation, but it’s far too easy for all of those struggles to seem past and pat once we’ve heard the same broad stories over and over again.

Coates unpacks the experience of slavery, racism, and being black in America in such a human, visceral way that it’s impossible to ignore.

“I have raised you to respect every human being as singular, and you must extend that same respect into the past. Slavery is not an indefinable mass of flesh. It is a particular, specific enslaved woman whose mind is active as your own, whose range of feeling is as vast as your own; who prefers the way the light falls in one particular spot in the woods, who enjoys fishing where the water eddies in a nearby stream, who loves her mother in her own complicated way, thinks her sister talks too loud, has a favorite cousin, a favorite season, who excels at dressmaking and knows, inside herself, that she is as intelligent and capable as anyone. ‘Slavery’ is this same woman born in a world that loudly proclaims its love of freedom and inscribes this love in its essential texts, a world in which these same professors hold this woman a slave, hold her mother a slave, her father a slave, her daughter a slave, and when this woman peers back into the generations all she sees is the enslaved. She can hope for more. She can imagine some future for her grandchildren. But when she dies the world—which is really the only world she can ever know—ends. For this woman, enslavement is not a parable. It is a damnation. It is the never-ending night. And the length of that night is most of our history. Never forget that we were enslaved in this country longer than we have been free. Never forget that for 250 years black people were born into chains—whole generations followed by more generations who knew nothing but chains.” – Ta-Nehisi Coates

Wow. Re-reading that now as I type it out for you still overwhelms my nervous system with awe. Because when my son was born I saw for the first time in my life how each human was a life who should be loved and cherished. And yet it’s so easy, and I have been guilty of, failing to see that humanity in each and every soul.

It doesn’t hurt that the language is flat out gorgeous.

The Pain and Poignancy of Parenthood

As you can see from the quotes above, this book is written as a letter from Coates to his son. That hits me especially hard right now as I’m trying to shape the brain, life, and values of my own young son. I worry for his future as I can see Coates worrying for the future of his son. Although my son is white. Coates writes to his son, “The price of error is higher for you than it is for your countrymen.” And I know that my son, who although he is the most important child to me in the world is not more important to the world than any other child, is far less likely to get shot for shoplifting or walking down the street.

The most impactful moment of this book, a book that is deeply impactful overall, is when Coates takes his son on an interview with a black woman whose son had been killed by a white man because he had refused to turn down his music. She wonders, “Had he not spoke back, spoke up, would he still be here?” And then she speaks to Coates’s son:

“You exist. You matter. You have value. You have every right to wear your hoodie, to play your music as loud as you want. You have every right to be you. And no one should deter you from being you. You have to be you. And you can never be afraid to be you.”

This woman who had lost her son because he stood up for himself, a loss that must feel like losing everything, still had the courage to encourage another young man to stand up for himself. Because it is the right thing to do. Although it carries a danger only she could truly understand in that moment, she knows the cost of giving in is too great. I hope I have the courage to teach my son to stand up for his convictions. I know when I tried to describe the dichotomy of trying to raise the best person and at the same time wanting him never to get hurt, I ended up crying.

What it’s Like to Feel Threatened

As a woman, I’m so used to feeling like a smaller mammal that I barely even register the ways that feeling affects my behavior on a daily basis. I’m not “playing the victim card,” it’s just my life experience. I’m careful about where I walk and when, who I sit next to on the bus, and taking the risk of challenging someone. I alter my language, the strongest tool I have, so that I do not offend, because offending someone bigger could get me hurt.

So when I read about the hundreds of sexist letters. No. They weren’t sexist, they were abusive. They might have been sexist too. The language they used was certainly ugly and usually only directed at women. When I read about the hundreds of abusive letters sent to female Seattle City Council members by sports fans angry they didn’t get their stadium, I was surprised to find myself shocked into silence. For a few minutes I could not even speak. I could barely move.

I tried to explain what I was feeling to my husband, but it was so big, so new to be talking about this feeling that I tried never to even think about. I was shocked at how ugly people can be (even though I know people can be ugly). I was angry that those men (and one woman) were being so childish. I was scared that they would feel so free to do something so public (it’s my assumption that all government emails are subject to potential disclosure) to public officials. If women of stature could be treated that way in a city I love…

When the subject was revisited in Crosscut a few days later, I finally found my voice. I knew I wanted to speak up, so I went to Twitter. I don’t have a huge following, but it’s the most public voice I have (that isn’t work-related). I tweeted this:

Seattle sexism: It’s real and has to stop https://t.co/aFHyWWho7C The events behind this story still chill my blood

— Isla McKetta, MFA (@islaisreading) May 12, 2016

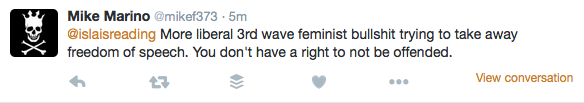

I was a little afraid to put myself out there, but I felt stronger for speaking. I got four retweets and five favorites – both high stats for me. And then I got this response:

I’d show you the embedded Twitter post instead of a screenshot, except he’d deleted it by the next day.

The response is banal enough. Kind of aggressive and accusative, and he puts some words in my mouth, but there’s nothing overtly threatening about it.

Except that’s not how I felt. Receiving this one response, even in a social media world I know is full of trolls looking to pick fights, I felt afraid. I dreaded the conversation spiraling. I worried what might come next and if I’d be the next recipient of some of the really ugly words being bandied about. I feared that my very dear coworkers would jump in on my side and just make the whole thing flare up even worse. I started considering how public my life is—listed phone number and address, easily accessible email, every vulnerability of my soul spelled out on this blog. I considered how secure my passwords are lest they get hacked. I worried for the safety of my son. I was inside a full-on fear response.

Maybe I was overthinking things or aggrandizing my own importance because after I summoned the courage/bluster to post this self defense designed to deflect not inflame:

Putting words in someone's mouth and then taking offense at those words seems especially small minded https://t.co/kY9Dk402JH

— Isla McKetta, MFA (@islaisreading) May 12, 2016

The conversation died out. Sometime after that he deleted his tweet. But the feeling of fear remained. And the next day I decided I would not be silenced:

Yesterday someone called me out on Twitter for having an opinion. And then deleted that tweet. Here it is. pic.twitter.com/yia78NE6oO

— Isla McKetta, MFA (@islaisreading) May 13, 2016

It is incumbent on me to use the power of language, the power that I have, to contradict wrongs. Those are values I hold very strongly—that I want to pass on to my son. Sometimes I need to do speak softly and sometimes I need to shout, but I need to show him that I have a voice and he has a voice and that our voices matter.

How This Changed My Feelings about #BlackLivesMatter

I’d spent a lot of time thinking that the Black Lives Matter movement was an outsized response to a real problem. I watched activists shouting down people who were on their side (like Bernie Sanders) just to be heard. And one activist reshaped history at a public event in a way I felt was downright dishonest. I started to agree with the #AllLivesMatter folks. Even though I knew that second movement was deafly trying to say “hey, your struggle isn’t all that special.” I shook my head and thought about more effective ways these activists could get their point about the continued effects of racism heard. I understood the privilege that comes with my light skin color in this society, but I did not understand what it felt like to be unprivileged. All lives matter, but not everyone has to fight for the respect we all deserve as humans.

After my tiny little Twitter battle, I realized that Black Lives Matter activists are finding their voices like I was. They’re so accustomed to living in a world where they carry the burdens of our society’s reactions to their skin color that they have every reason to believe if they engage in a civil discourse about police brutality that too often leads to deaths these activists will not be heard.

I still think the movement hasn’t found the way to communicate that will actually create institutional change, but now I wonder if that’s their goal. Perhaps they’re just saying, in a world where they’re pretty sure change is impossible, “I exist. I matter.” And they do.

“I am speaking to you as I always have—as the sober and serious man I have always wanted you to be, who does not apologize for his human feelings, who does not make excuses for his height, his long arms, his beautiful smile. You are growing into consciousness, and my wish for you is that you feel no need to constrict yourself to make other people comfortable.” – Ta-Nehisi Coates

So, Am I a Racist?

This probably isn’t even the right question, but yes, as much as I wish I just saw color as a descriptor, I am racist in some ways. I try to challenge myself when stereotypes bubble to the surface, but, no matter how much my friend group may look like a Benetton ad, I have a lot of work to do before I can even begin to consider myself post racial.

I hope that more people will read books like Between the World and Me and think deeply about how we all relate to one another. And if even one more person could write a book this excellent that taught me this much…

If you want to interrogate yourself, or even just read some really gorgeous writing, pick up a copy of Between the World and Me. Better yet, buy two copies. Give one to a friend who has a different life experience than you do. Then ask them to share their point of view with you. You’ll learn a lot by listening.

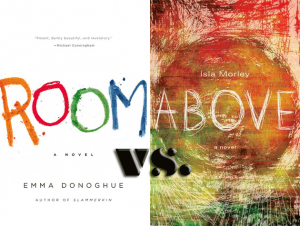

Initially, I was reluctant to read Emma Donoghue’s Room, because I’d recently read Above by Isla Morley and I was pretty sure there were only so many “kidnapped woman imprisoned for years bears the child of her kidnapper/rapist” stories this new mom could take. But I found Room in one of our neighborhood Little Free Libraries and couldn’t resist. As similar as the stories sound at first blush, the books could not be more different. Except that I loved them both.

Initially, I was reluctant to read Emma Donoghue’s Room, because I’d recently read Above by Isla Morley and I was pretty sure there were only so many “kidnapped woman imprisoned for years bears the child of her kidnapper/rapist” stories this new mom could take. But I found Room in one of our neighborhood Little Free Libraries and couldn’t resist. As similar as the stories sound at first blush, the books could not be more different. Except that I loved them both. I have no clue why I’ve been drawn to essays lately, but when I saw Living, Thinking, Looking at the bookstore, I thought “I liked The Summer Without Men, maybe I’ll like Siri Hustvedt’s essays, too.” I had no idea that I was on the verge of finding my authorial twin and a source of constant inspiration.

I have no clue why I’ve been drawn to essays lately, but when I saw Living, Thinking, Looking at the bookstore, I thought “I liked The Summer Without Men, maybe I’ll like Siri Hustvedt’s essays, too.” I had no idea that I was on the verge of finding my authorial twin and a source of constant inspiration.

One of the things I admire most about dystopian and fantasy novels is the author’s ability to create a whole other world. Few have done this better than Hugh Howey in Wool, the first book in the Silo series.

One of the things I admire most about dystopian and fantasy novels is the author’s ability to create a whole other world. Few have done this better than Hugh Howey in Wool, the first book in the Silo series. The first time I read The Pearl by John Steinbeck was in junior high. It was the book that made me hate symbolism. All I can remember is my teacher going on and on about the pearl of great price—a litany that landed with such a thud in my heart that I decided never to study literature lest I come to hate books.

The first time I read The Pearl by John Steinbeck was in junior high. It was the book that made me hate symbolism. All I can remember is my teacher going on and on about the pearl of great price—a litany that landed with such a thud in my heart that I decided never to study literature lest I come to hate books.