I was delighted when my review copy of Carrying Albert Home by Homer Hickam arrived in the mail. Not only was I not expecting it, but I’d felt such a close connection with the film October Sky (based on Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys) that I was looking forward to learning more about his family. And the timing could not have been more perfect.

I was delighted when my review copy of Carrying Albert Home by Homer Hickam arrived in the mail. Not only was I not expecting it, but I’d felt such a close connection with the film October Sky (based on Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys) that I was looking forward to learning more about his family. And the timing could not have been more perfect.

Family Epic: Novel or Memoir?

Billed as “The Somewhat True Story of A Man, His Wife, and Her Alligator,” Carrying Albert Home is what Hickam calls a “family epic.” Coming from a family of storytellers, I’m very familiar with this genre—although I hadn’t before considered it could be a genre—and this book helped me understand what I loved so much about the novel and film Big Fish.

We’ve all been told stories of how our forefathers walked dozens of mile to school in snow up to their necks and uphill both ways. The exaggeration of these tales somehow helps us remember undercurrents of who our ancestors were. Hickam captures the spirit of family lore with the epic tale of his parents’ journey to deliver their pet alligator back to Florida.

Although the details are too good to be true, I wanted them to be, and as Homer (the elder) and Elsie encounter John Steinbeck, Communists, bootleggers, and bank robbers during their quest I felt like I was getting to know the core of those two characters—Homer who endures all and Elsie who wants to experience every possible excitement life has to offer. Although the book is packed with greater truths, I was so glad I didn’t have to care if the details of the story were accurate.

The Art of Plotting a Journey

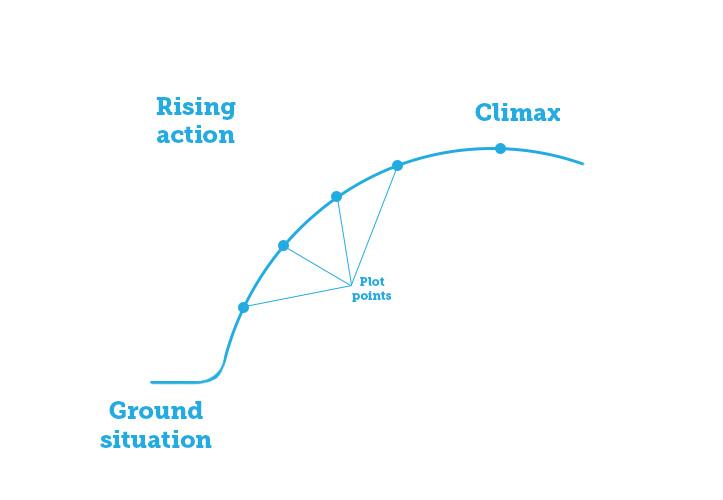

Hickam’s folksy storytelling style and the ever-escalating events reminded me of that other Homer’s The Odyssey and like that classic work, this book is a textbook example of Aristotle’s plot arc.

The ground situation—Homer living with a restless Elsie in Coalwood with a rapidly growing alligator—turns into a story when they set on the road to deliver Albert home. Each new plot complication (the aforementioned bootleggers, bank robbers, and more) is a struggle Homer and Elsie have to overcome to get Albert back where he belongs.

What makes this book an exceedingly good example of how to structure a story, though, is how clearly you can trace not just Albert’s physical journey, but also the emotional journeys of Homer and Elsie. Hickam uses each of the plot points is a new opportunity to examine and shift their desires and the possible outcome of their love story.

If you want to get even headier about how this book exemplifies story structure, read up about Joseph Campbell’s monomyth and use that information to trace Elsie’s “hero’s journey.” It’s an excellent exercise to learn how to refine a plot.

My Own Family’s Epic

When I said I felt a close connection with October Sky, it’s because my grandfather was a coal miner who broke free from his small town by becoming a chemical engineer like (a generation later) Hickam broke free from his coal mining destiny by becoming a rocket scientist. But that’s the boring version of my Djiedo’s story. In his self-published memoir My First 80 Years, Djiedo (Dr. John J. McKetta) details a wild lifetime of anecdotes starring everything from beating Perry Como in a singing contest to being bitten by a blue-footed booby.

Although some of the stories seem far too large to be true, I want them to be, and they’ve become such a part of the family lore that I want my son to know the stories as they are—somewhat outsized versions of a fabulous life. And I get a special chance to make him part of that epic as we all converge on Austin this October to celebrate Djiedo’s 100th birthday. The coal mining boxer-engineer-trumpeter-presidential advisor will be feted by a family including my father the pilot-sign carver-forester-economist-bookseller and me the novelist-marketer-reviewer-mother (as a younger member of the family I still have some time to catch up on my dashes). Storytellers all, whatever unlikely events happen during the weekend celebration, the version we later remember will be one hell of a story and I can’t wait to enlarge and improve upon it as I retell it to my son over the years.

Happy birthday, Djiedo! Thanks for setting a fantastic example. May all our stories be as long and rich as yours.

If you want to set on the adventure of a lifetime with Hickam’s family, pick up a copy of Carrying Albert Home from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

I picked up Enon by Paul Harding on a rare trip to the bookstore in the first few weeks of my son’s life. I did not know then what the book was about, but I had so enjoyed Tinkers that I was glad to take a chance on what I knew would be a solidly written piece of fiction. I did not know that it was going to make me question how emotion is and should be conveyed in literature.

I picked up Enon by Paul Harding on a rare trip to the bookstore in the first few weeks of my son’s life. I did not know then what the book was about, but I had so enjoyed Tinkers that I was glad to take a chance on what I knew would be a solidly written piece of fiction. I did not know that it was going to make me question how emotion is and should be conveyed in literature. Reading the first page of the review copy of Melissa DeCarlo’s The Art of Crash Landing where self-proclaimed “fuckup savant” Mattie Wallace details how long it takes to cram your entire life into plastic garbage bags and outline some of the circumstances that got her there, I cringed. I thought, “Oh, great, a self-indulgent, first-person narrative about how the world done her wrong.” But I could not have been more wrong, and instead The Art of Crash Landing turned into a wild ride through a life wasted where redemption and forgiveness burn on the horizon.

Reading the first page of the review copy of Melissa DeCarlo’s The Art of Crash Landing where self-proclaimed “fuckup savant” Mattie Wallace details how long it takes to cram your entire life into plastic garbage bags and outline some of the circumstances that got her there, I cringed. I thought, “Oh, great, a self-indulgent, first-person narrative about how the world done her wrong.” But I could not have been more wrong, and instead The Art of Crash Landing turned into a wild ride through a life wasted where redemption and forgiveness burn on the horizon. How many ways can you write about widowhood? In Wet Silence: Poems about Hindu Widows, Sweta Srivastava Vikram explores every nuance of what life is like for a Hindu widow in India. It’s as much a human exploration as a cultural one as Vikram delves into the aftermath of the complex relationships that underlie arranged marriages. Some of the widows in this collection are devastated that their beloved husbands have passed. Others rejoice in their new freedom from abuse and adultery. Still others face new complications in their relationships with the families to which they have now become burdensome.

How many ways can you write about widowhood? In Wet Silence: Poems about Hindu Widows, Sweta Srivastava Vikram explores every nuance of what life is like for a Hindu widow in India. It’s as much a human exploration as a cultural one as Vikram delves into the aftermath of the complex relationships that underlie arranged marriages. Some of the widows in this collection are devastated that their beloved husbands have passed. Others rejoice in their new freedom from abuse and adultery. Still others face new complications in their relationships with the families to which they have now become burdensome. I’ve written more extensively about this book

I’ve written more extensively about this book

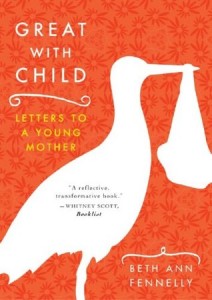

One of the blurbs on this book reads, “The best book ever to give for a baby shower” and I am so grateful that a writer friend gave me a copy at one of my baby showers. Originally written as a series of letters from Beth Ann Fennelly (then a newish parent) to a dear friend, it’s easy to feel like you are the dear friend as you read Fennelly’s stories about parenting and gentle advice. Advice is such a tricky thing for the pregnant woman (it’s everywhere but so rarely does an advisor allow space for the advisee’s experience rather than rehashing theirs) and Fennelly gets it just right. This poet writes beautifully about everything from conception to labor, with the occasional book recommendation along the way.

One of the blurbs on this book reads, “The best book ever to give for a baby shower” and I am so grateful that a writer friend gave me a copy at one of my baby showers. Originally written as a series of letters from Beth Ann Fennelly (then a newish parent) to a dear friend, it’s easy to feel like you are the dear friend as you read Fennelly’s stories about parenting and gentle advice. Advice is such a tricky thing for the pregnant woman (it’s everywhere but so rarely does an advisor allow space for the advisee’s experience rather than rehashing theirs) and Fennelly gets it just right. This poet writes beautifully about everything from conception to labor, with the occasional book recommendation along the way.