It’s not hard to trigger a newish mom’s “what would happen to my family if something happened to me” fears, but it is hard to sustain a quiet story over 350 pages. In In the Quiet, Eliza Henry-Jones does both so beautifully that not only did I feel immersed rather than manipulated, but I stayed up many hours past bedtime to surrender to the world of this book and to the life of this family.

It’s not hard to trigger a newish mom’s “what would happen to my family if something happened to me” fears, but it is hard to sustain a quiet story over 350 pages. In In the Quiet, Eliza Henry-Jones does both so beautifully that not only did I feel immersed rather than manipulated, but I stayed up many hours past bedtime to surrender to the world of this book and to the life of this family.

When the book begins, the narrator, Cate Carlton, is already dead and looking in on her family in poignant moment after poignant moment—like when her daughter (Jessa) gruffly stonewalls a grief counselor or a son (Rafferty) pulls a box of the last flowers Cate ever picked from beneath his bed. We don’t know how Cate died—the detail that ends up forming the central mystery of the novel—but the family moments are so touching and real that we quickly focus all our attention there and nearly forget that Cate is also missing this critical piece of information. Perhaps because the family story is so strong and each member so individual, the book is satisfying all the way through and I only occasionally noticed the bumpy edge of a clue being dropped on the page and when all is gently revealed, I realized I already had all the information that truly mattered.

The Objective Correlative

The jacket copy of In the Quiettalks about the grief this family alternately endures and learns to cope with, but the story is a lot richer than that. There are daily rhythms to be maintained and reinvented—specifically (and symbolically), there are horses to be fed, trained, and potentially sold to pay some of the family’s expenses.

One horse, Opal, is the most valuable, the most wild, and is lost to the family around the time of Cate’s death. Bass, Cate’s widower husband, is looking for Opal because she could help ease the family’s financial burden. Family friend Laura cares for Opal the way she once cared for Cate. Jessa’s relationship with Opal is the most dynamic—clinging hard to the horse even as others are trying to get Jessa to let go and ultimately making some strong, hard decisions. All this while Rafferty shies away from Opal for reasons that don’t become clear until much later. I thought I knew why pretty early. I was deliciously and wonderfully wrong.

By using Opal as an objective correlative like this, Henry-Jones’s displacing the family’s emotion onto the horse. Not only is this something that happens frequently in grief (you should have seen my family with a pile of jewelry and a stop watch after my grandmother’s death), this literary device allows Henry-Jones to explore on the surface what’s happening deep inside each of her characters. This is one crucial element of what makes In the Quiet heartfeltly intelligent rather than sappy and sad.

Characterization

If I had to pick a favorite character in this book, I couldn’t. And if I had to pick a least favorite, I also could not. Both, to me, are a sign that Henry-Jones’s created a well-written, round cast of characters by exploring their humanity and idiosyncrasies at a depth which does the characters, and the reader, justice.

If we look for a moment just at Beatrice and Laura, the two women who grow closer to Bass after his wife’s death, the healing and stealing of the widower being a trope in both literature and life, we find strong, interesting characters with motivations far beyond getting the guy. That’s wonderful in its own right, but it’s much more extraordinary when you consider that this book is being told first-person through the eyes of the woman who lost Bass when she died. Cate’s exploration of her history with both of these women, one her sister and the other her best friend, gives an understanding of the gifts they bring to the world of the book and to the wounds that they themselves are trying to heal. It also gives Cate a chance to heal and for us to care about and cheer for both women.

Narrative Time

As with blending bits of Cate’s history with Laura into the narrative of the present, Henry-Jones gently drops bits of flashback amidst the forward-moving momentum of this book. The result is a lovely, patterned collage of what Cate is seeing after her death and what she experienced while living. I have not taken the time to diagram the placement of the flashbacks, but the book’s rhythm is so soothing that I’d wager they happen at very regular intervals. The mastery of Henry-Jones’s prose is that the rhythm doesn’t feel episodic or repetitive and I don’t think most readers would notice it unless they went looking.

Tears were shed in the reading of this book, but not in the way I’d expected. Instead, my husband found me weeping only as I was wrapping up the final pages. Because of the craft and emotional honesty of In the Quiet, I was so engaged in the tender family portraits that I scarcely had time to mourn the family’s loss until the end. Or maybe it was that the family didn’t really lose their mom until the end. Or at least she didn’t lose them.

In the Quiet is a quiet, beautifully crafted, engaging book. I’ll admit I put off reading it because I didn’t know how good it would be. Don’t make the same mistake.

If you want to see how to transform a potential tear-jerker into a work of literature, or just read a really heartfelt story, pick up a copy of In the Quiet.

Of all the things that have happened in the months since Trump was inaugurated, none has hit me as hard as the Muslim ban. A lot of things have upset me, but that one struck at my core values. For days after it was announced that America was no longer going to be the land of opportunity for all but instead was going to start openly turning away legitimate immigrants en masse, I was glued to the news and Twitter just waiting to see if we’d come to our senses. I was so tuned into events that I tuned out of my family and simply waited.

Of all the things that have happened in the months since Trump was inaugurated, none has hit me as hard as the Muslim ban. A lot of things have upset me, but that one struck at my core values. For days after it was announced that America was no longer going to be the land of opportunity for all but instead was going to start openly turning away legitimate immigrants en masse, I was glued to the news and Twitter just waiting to see if we’d come to our senses. I was so tuned into events that I tuned out of my family and simply waited. Speaking of people we don’t treat all that well, I’m glad we’re finally having more concerted discussions about race. We need to do more. I’ve spent a lot of time lately thinking about

Speaking of people we don’t treat all that well, I’m glad we’re finally having more concerted discussions about race. We need to do more. I’ve spent a lot of time lately thinking about  One of the most reassuring and also unnerving things about Walks with Walser, the book I’m currently reading, is seeing that art can both endure terrible times but that it can also remove itself completely from life. Chronicling conversations during the 27 years Robert Walser spent in an asylum after a breakdown, this book spans World War II and yet, because it occurs in Switzerland, barely even acknowledges what’s happening next door. There are some really gorgeous reflections on the life of an artist in this book, but it’s also an important reminder to me that I am not content to check out on the real world. Though I could benefit from a few more long walks.

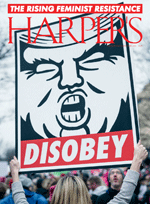

One of the most reassuring and also unnerving things about Walks with Walser, the book I’m currently reading, is seeing that art can both endure terrible times but that it can also remove itself completely from life. Chronicling conversations during the 27 years Robert Walser spent in an asylum after a breakdown, this book spans World War II and yet, because it occurs in Switzerland, barely even acknowledges what’s happening next door. There are some really gorgeous reflections on the life of an artist in this book, but it’s also an important reminder to me that I am not content to check out on the real world. Though I could benefit from a few more long walks. A former student of political science, I’ve long subscribed to Harper’s to keep my political muscle active. It’s been an important lifeline since the election. I’m not one of those liberals who was completely surprised Trump won, I think the Democratic Party ignored the growing dissatisfaction of lower-income and blue collar Americans. But I am appalled that Trump was elected.

A former student of political science, I’ve long subscribed to Harper’s to keep my political muscle active. It’s been an important lifeline since the election. I’m not one of those liberals who was completely surprised Trump won, I think the Democratic Party ignored the growing dissatisfaction of lower-income and blue collar Americans. But I am appalled that Trump was elected. I thought I was escaping back into fiction when I pulled The Assault off my bookshelf. I remembered Arenas’ languid, gorgeous language and I really needed a little kick to get back to writing. But of course this Cuban-born novelist who was persecuted by his government is famous for writing about that experience.

I thought I was escaping back into fiction when I pulled The Assault off my bookshelf. I remembered Arenas’ languid, gorgeous language and I really needed a little kick to get back to writing. But of course this Cuban-born novelist who was persecuted by his government is famous for writing about that experience. West of Here is not a dystopian book. That might be why I sandwiched it somewhere in the middle of all this heavy reading. In fact, it contains elements of the utopias white people wrote about in the 19th and early 20th centuries as explorers went off to conquer new lands and found paradisaical locales with unlimited natural resources. It also contains stories of the people who were already here and a view into what life is like in those same paradises 100 years later. I love reading Jonathan Evison’s descriptions of places I love. I love his understanding of the simplicity and complexity of human motivations. And I love that a strange mystical vein runs through the story. Dams go up, dams come down. People settle, people perish, people endure.

West of Here is not a dystopian book. That might be why I sandwiched it somewhere in the middle of all this heavy reading. In fact, it contains elements of the utopias white people wrote about in the 19th and early 20th centuries as explorers went off to conquer new lands and found paradisaical locales with unlimited natural resources. It also contains stories of the people who were already here and a view into what life is like in those same paradises 100 years later. I love reading Jonathan Evison’s descriptions of places I love. I love his understanding of the simplicity and complexity of human motivations. And I love that a strange mystical vein runs through the story. Dams go up, dams come down. People settle, people perish, people endure.

Wicked little books. They’re all I read these days when on a good night I can manage 20 pages and most nights I can’t even remember any of what I read the night before. By wicked little, I mean very short, except in the case of The Redemption of Galen Pike by Carys Davies which is short, but it is also wicked in the most delicious of ways. The stories are compact enough that I could read a few each night if I wanted to, but, more importantly, they are dincredibly well drawn which made them oh-so-memorable. Perfect for a newish mom with a dark sense of humor and an interest in the baser side of human consciousness.

Wicked little books. They’re all I read these days when on a good night I can manage 20 pages and most nights I can’t even remember any of what I read the night before. By wicked little, I mean very short, except in the case of The Redemption of Galen Pike by Carys Davies which is short, but it is also wicked in the most delicious of ways. The stories are compact enough that I could read a few each night if I wanted to, but, more importantly, they are dincredibly well drawn which made them oh-so-memorable. Perfect for a newish mom with a dark sense of humor and an interest in the baser side of human consciousness. Was it magic or serendipity that a copy of The Magicians by Lev Grossman showed up in my local Little Free Library the very same week that the related Syfy series showed up on Netflix? I’m not certain, but I can say that reading the book while binge watching the series has me a little convinced that there is magic in the world around me, even if my Popper finger movements haven’t yet led to the dishwasher loading itself. It’s rare that I like an adaptation as much as the book, but experiencing the two together has added a whole new layer of enjoyment to the story and characters for me.

Was it magic or serendipity that a copy of The Magicians by Lev Grossman showed up in my local Little Free Library the very same week that the related Syfy series showed up on Netflix? I’m not certain, but I can say that reading the book while binge watching the series has me a little convinced that there is magic in the world around me, even if my Popper finger movements haven’t yet led to the dishwasher loading itself. It’s rare that I like an adaptation as much as the book, but experiencing the two together has added a whole new layer of enjoyment to the story and characters for me. It’s inauguration day! Regardless of how you feel about the outcome of the election, I’m willing to bet your feelings are strong. Mine are and I’m so glad Leaving Kent State by Sabrina Fedel entered my heart and my home when it did because it made me less scared to stand up for my beliefs and turned me into a better human overall.

It’s inauguration day! Regardless of how you feel about the outcome of the election, I’m willing to bet your feelings are strong. Mine are and I’m so glad Leaving Kent State by Sabrina Fedel entered my heart and my home when it did because it made me less scared to stand up for my beliefs and turned me into a better human overall.