These books have in common that they all deal with the effects of the Balkan War on their characters, and I came to wonder, are there contemporary Balkan books that don’t? I am thinking about definition a lot lately and the roles we put on ourselves and the roles others put on us. I could understand if every contemporary writer in any way associated with the region only wrote about the war—war has a huge and lasting impact—but I suspect that there are writers who deal more peripherally with the war (if at all) and I am interested to know if their work is being translated. I am curious about the filters that are being applied by translators and agents and editors and publishing houses to the way I see the Balkans. How horrible it would be if writers from the former Yugoslavia were given the impression that the world is only interested in their work if it is about the Balkan War. How limiting for their potential audience.

Perhaps I’m wondering how much daily life in the tourist areas of Dubrovnik is affected by the war or I am curious about the lives of our soon-to-be landlords. Perhaps I feel a little guilty that I have gone from seeing Plitvice as the place my grandmother most loved to seeing it as the place where the first shot of the war was fired. Perhaps I am thinking about my own writing and the lack of control I feel in a world where the success of a writer is still determined by so many external actors (and I don’t mean readers). In learning more about Croatia and its neighbors, I have read some very good books, including Shards, but I keep feeling like I’m only able to experience through these books one aspect of a rich group of cultures. I guess that’s what the plane ticket is for…

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of Shards from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

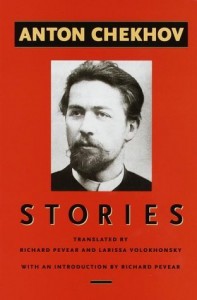

Chekhov names the nature of Olenka’s character early in the story in the following passage: “She was always fond of some one [sic], and could not exist without loving.” He then mentions some of the family members she has loved. But prior to this, her husband, Ivan Petrovitch Kukin, (aka Vanitchka) has had a large blowup about the vulgarity of the patrons of the story. I was drawn into the drama of Kukin and didn’t see this first clue, the subtle unfurling of Olenka’s personality. When she first parrots his opinion, “‘But do you suppose the public understands that?’” I thought we were seeing an action she would habitually take, but I didn’t yet realize this was the key to her nature. It isn’t until Chekhov revealed that the actors referred to her as “Vanitchka and I” that I got the point.

Chekhov names the nature of Olenka’s character early in the story in the following passage: “She was always fond of some one [sic], and could not exist without loving.” He then mentions some of the family members she has loved. But prior to this, her husband, Ivan Petrovitch Kukin, (aka Vanitchka) has had a large blowup about the vulgarity of the patrons of the story. I was drawn into the drama of Kukin and didn’t see this first clue, the subtle unfurling of Olenka’s personality. When she first parrots his opinion, “‘But do you suppose the public understands that?’” I thought we were seeing an action she would habitually take, but I didn’t yet realize this was the key to her nature. It isn’t until Chekhov revealed that the actors referred to her as “Vanitchka and I” that I got the point.