I might be the last person on the planet to actually read Maya Angelou’s Poems, but I’ve finally done it and I’m so glad I waited because in reading this book aloud to my newborn son I was able to fully appreciate not only the content of her writing but the musicality as well.

I might be the last person on the planet to actually read Maya Angelou’s Poems, but I’ve finally done it and I’m so glad I waited because in reading this book aloud to my newborn son I was able to fully appreciate not only the content of her writing but the musicality as well.

Rhyme and Cadence

Is there anything more enjoyable to read aloud than intelligently rhymed poetry? I’ve been stuck in a rhyming rut with my own work for over a year now (where the rhymes come—dumb or not—and I can’t stop them no matter what I try) and it was such a relief and an inspiration to see how well Angelou works with rhyme and its cousin, cadence.

Part of the beauty of her rhyme is that she breaks from traditional rhyme schemes. While the first stanza of “Song for the Old Ones” she plays with a variation of the classic abab pattern:

My Fathers sit on benches

their flesh count every plank

the slats leave dents of darkness

deep in their withered flanks

Where benches is barely a slant rhyme with darkness but plank and flanks could hardly rhyme more closely. But in the second stanza, she abandons what would be the “c” in the cdcd rhyme you’d expect:

They nod like broken candles

all waxed and burnt profound,

they say, “It’s understanding

that makes the world go round.”

Breaking with those conventions also means breaking up the sometimes sing-song character of rhyme and made for an enjoyable (and instructive) read.

Repetition

Part of Angelou’s musicality is how she’s unafraid to repeat a refrain to the point of near exhaustion. In “Picken Em Up and Layin Em Down” she repeats the title phrase twelve times in two pages. In my own work I’d edit that right on down to a modest number that gives a hint of what I’m saying. But here it’s the sheer excess that works. Not only do you see the narrator’s trans-American journey of tomcatting, but you get to feel its never-ending quality. And for me the phrase repeated enough times to open up a sad, empty feeling beneath the behavior.

Angelou uses this excess of repetition equally artfully in “Ain’t that Bad?” where the refrain shifts just enough to keep me engaged and watching for what she’ll do next:

Now ain’t they bad?

And ain’t they Black?

And ain’t they Black?

And ain’t they Bad?

And ain’t they bad?

And ain’t they Black?

And ain’t they fine?

There’s a complexity of feeling to these lines that evolves as the repetition shifts and I can’t imagine a better way to express that.

Accessible Language

While I’m not a huge fan of overly highbrow language in poetry, I was still surprised by how colloquial Angelou’s poetry can get. And I loved it. From the hybrid verb/adjectives of “Little Girl Speakings” where she channels a little girl admiring her mother’s “cookinger” skills with pie to her frequent use of contractions, she’s unafraid to use just the right word or slang to catch the voice of her narrator and/or audience. This draws attention to the voice. It also shows that the manner of someone’s speech does not in any way indicate the depth of their thoughts or feelings—an important lesson for intellectual elitists like me.

As with everything else discussed here today, it’s clear that Angelou is using those colloquialisms as a tool and because she is, she has a much wider range of language at her disposal. This freedom is something I’d like to experiment with in my own work. I can only hope to capture as much authenticity with my language as she does.

Re-imagining Imagery

Just because Angelou (sometimes) uses simpler language does not mean that her poetry is in any way simplistic. The way she uses images like “wombed room” and “brain-dust / of rainbows” made every little synapse in my head wake up and engage. Sometimes all it took was a slight shift of phrase as in “little dyings” to rock my linguistic world, but Angelou showed me how much can be done with the everyday blocks of language. Of course it can be very difficult to find exactly the right image or a new way of expressing something without making a poem all about that one phrase, but I have a lot to learn from Angelou about how to do it well.

Broadening My Perspective

As a white woman, the things I have teach my son about the world are limited. That’s not because I’m white or because I’m a woman but because I have one set of life experiences to share. And the lily white shade of my reading tastes was never more obvious to me than when I was teaching a class at Mary’s Place, a local shelter for homeless women. Although I brought in textbook-ready poems like “We Real Cool” by Geraldine Brooks, I failed to really venture into anything that wasn’t already in the mainstream—something my students were (rightly) quick to point out.

Reading Angelou opened up a world of understanding to me of both how an African American woman might see the world and also some historical events that were merely history book entries to me before. Yes, her work has been accepted into the mainstream, but Poems allowed me to read far beyond “Caged Bird” (which is a gorgeous starting point to discussing race in America, but only a starting point) to the pained, angry cries of “Africa”:

brigands ungentled

icicle bold

took her young daughters

sold her strong sons

churched her with Jesus

And I loved how she juxtaposed that with “America,” starting with how “The gold of her promise / has never been mined” and delving into the abundance and justice that so many never experience. And I’ll never look at Gone with the Wind (or Antebellum history) the same way after reading “Miss Scarlett, Mr. Rhett and Other Latter-Day Saints.”

Am I sorry that I waited so long to read Maya Angelou? Not really. I’ve loved stumbling through poetry on my quest to understand it and I’ve found some real gems along the way. But I’m sure glad that I read Angelou now. I can’t wait to incorporate what I’ve learned as I edit my growing manuscript of pregnancy and early parenting poetry.

If you want to rediscover language yourself, pick up a copy of Maya Angelou’s Poems from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

I was delighted when my review copy of Carrying Albert Home by Homer Hickam arrived in the mail. Not only was I not expecting it, but I’d felt such a close connection with the film October Sky (based on Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys) that I was looking forward to learning more about his family. And the timing could not have been more perfect.

I was delighted when my review copy of Carrying Albert Home by Homer Hickam arrived in the mail. Not only was I not expecting it, but I’d felt such a close connection with the film October Sky (based on Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys) that I was looking forward to learning more about his family. And the timing could not have been more perfect.

I picked up Enon by Paul Harding on a rare trip to the bookstore in the first few weeks of my son’s life. I did not know then what the book was about, but I had so enjoyed Tinkers that I was glad to take a chance on what I knew would be a solidly written piece of fiction. I did not know that it was going to make me question how emotion is and should be conveyed in literature.

I picked up Enon by Paul Harding on a rare trip to the bookstore in the first few weeks of my son’s life. I did not know then what the book was about, but I had so enjoyed Tinkers that I was glad to take a chance on what I knew would be a solidly written piece of fiction. I did not know that it was going to make me question how emotion is and should be conveyed in literature. Reading the first page of the review copy of Melissa DeCarlo’s The Art of Crash Landing where self-proclaimed “fuckup savant” Mattie Wallace details how long it takes to cram your entire life into plastic garbage bags and outline some of the circumstances that got her there, I cringed. I thought, “Oh, great, a self-indulgent, first-person narrative about how the world done her wrong.” But I could not have been more wrong, and instead The Art of Crash Landing turned into a wild ride through a life wasted where redemption and forgiveness burn on the horizon.

Reading the first page of the review copy of Melissa DeCarlo’s The Art of Crash Landing where self-proclaimed “fuckup savant” Mattie Wallace details how long it takes to cram your entire life into plastic garbage bags and outline some of the circumstances that got her there, I cringed. I thought, “Oh, great, a self-indulgent, first-person narrative about how the world done her wrong.” But I could not have been more wrong, and instead The Art of Crash Landing turned into a wild ride through a life wasted where redemption and forgiveness burn on the horizon. I’ve written more extensively about this book

I’ve written more extensively about this book

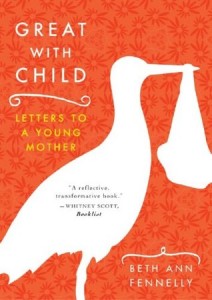

One of the blurbs on this book reads, “The best book ever to give for a baby shower” and I am so grateful that a writer friend gave me a copy at one of my baby showers. Originally written as a series of letters from Beth Ann Fennelly (then a newish parent) to a dear friend, it’s easy to feel like you are the dear friend as you read Fennelly’s stories about parenting and gentle advice. Advice is such a tricky thing for the pregnant woman (it’s everywhere but so rarely does an advisor allow space for the advisee’s experience rather than rehashing theirs) and Fennelly gets it just right. This poet writes beautifully about everything from conception to labor, with the occasional book recommendation along the way.

One of the blurbs on this book reads, “The best book ever to give for a baby shower” and I am so grateful that a writer friend gave me a copy at one of my baby showers. Originally written as a series of letters from Beth Ann Fennelly (then a newish parent) to a dear friend, it’s easy to feel like you are the dear friend as you read Fennelly’s stories about parenting and gentle advice. Advice is such a tricky thing for the pregnant woman (it’s everywhere but so rarely does an advisor allow space for the advisee’s experience rather than rehashing theirs) and Fennelly gets it just right. This poet writes beautifully about everything from conception to labor, with the occasional book recommendation along the way.