Shifting Omniscient Perspective

The way the omniscient perspective in the novel dips into the mind of one character and then another with only a paragraph break for separation gives the narration an almost choral effect as character after character muses through their own thoughts and then comments on the action of the novel. The muse, comment, muse pattern in the first chapter opens up space within the novel where the characters come to life even though the action is sparse and takes place over a short period of time. On page 64, the narrator tells us Mrs. Ramsay is knitting and then gives us her thoughts as they wander to “How could any Lord have made this world….With her mind she had always seized the fact that there is no reason, order, justice: but suffering, death, the poor” and then the narrator returns us to the image of her as she “knitted with firm composure.” Then back to musing and back to knitting. As a reader I feel like I know Mrs. Ramsay in a way I would not if I were to see her knitting in a chair. Because the narrator consistently brings the reader back to the action, the piece still feels grounded. This is something I explored in my novel Polska, 1994. I worked to open up spaces inside the narrative where characters can be and show more of themselves.

The Voice of the House

Whereas the first chapter of To the Lighthouse is populated with the various perspectives and internal voices of characters, the second chapter is nearly devoid of them. The narration focuses on the house itself (its rooms, its furnishings, and its environment) and a result the house and the story feel empty and sad. The reader feels that the Ramsay family and in particular Mrs. Ramsay was the soul of the house. The reader feels the loss of Mrs. Ramsay to the extent that the magic of the house cannot be regained even when the Ramsay family returns in the third chapter.

Repetition

Woolf uses repetition as Lily frequently mentally notes something that Mrs. Ramsey has just noted (e.g. that Paul and Minta are engaged). Lily also comes back to the image of the tree in her painting over and over again as dinner progresses and she decides to move it more to the middle. As the tree comes up again and again, the image is more concrete in the reader’s mind. These things that are repeated take on a greater significance than if they were merely mentioned once, and Lily’s echo of Mrs. Ramsay not only enforces the general understanding of the group but it also shows the similarity in character between Mrs. Ramsay and Lily. I worked with repetition in Murmur of the River. There are a few key scenes that happen twice but in two different ways and this repetition shows how the world around Magda is changing and also how Magda’s interaction with her world is changing.

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of To the Lighthouse from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

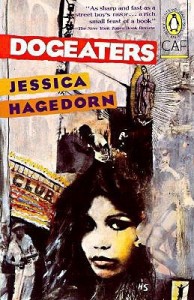

I’m thinking a lot about the feel of foreign words on the tongue and in print lately, so I want to talk about Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters. She uses Tagalog and Spanish words throughout this novel set in the Phillipines. Most often these phrases are used in dialogue and consist of exclamations, family designations, or food. Hagedorn sets aside the words for the reader by using italics, but it is clear that the intermingling of these words would occur naturally in the characters’ speech. These words lend the story authenticity, but they can also interfere with the reader’s understanding of the story.

I’m thinking a lot about the feel of foreign words on the tongue and in print lately, so I want to talk about Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters. She uses Tagalog and Spanish words throughout this novel set in the Phillipines. Most often these phrases are used in dialogue and consist of exclamations, family designations, or food. Hagedorn sets aside the words for the reader by using italics, but it is clear that the intermingling of these words would occur naturally in the characters’ speech. These words lend the story authenticity, but they can also interfere with the reader’s understanding of the story.