Who will we become? Is the longing for something greater in life something we should chase or should we be happy with what we have? When farm boy Orno Tarcher meets the worldly Marshall Emerson on Orno’s first day at Columbia in For Kings and Planets by Ethan Canin, these are the questions that are set in motion. And if the book had lived up to that struggle, I would have been thrilled.

Who will we become? Is the longing for something greater in life something we should chase or should we be happy with what we have? When farm boy Orno Tarcher meets the worldly Marshall Emerson on Orno’s first day at Columbia in For Kings and Planets by Ethan Canin, these are the questions that are set in motion. And if the book had lived up to that struggle, I would have been thrilled.I keep wondering why I was so critical of this book as I was reading it. It spoke to a struggle I face every day. The language was pleasant and the central metaphor was mercifully subtle. It featured characters who felt deeply familiar to me. But there’s another, much deeper reason I could not love this book…

My Struggle

I wrote last week about my desire for an unwritten life. But I also want to feel grounded in myself. Throughout their college experience, Marshall pushes Orno to do something more, something greater. And Orno pushes himself to accept his own limitations. Hell, not even limitations. Orno pushes himself to enjoy the more grounded life he’s drawn to. He experiments with Marshall’s kind of life and he loves his friend dearly, but he knows it isn’t right for him.

I don’t know yet what’s right for me. I know I need to create, but in the past month I couldn’t point even to a poem that I’ve started, at least nothing for myself. The dreams and projects are building up inside me but something is holding me back. And while I’d been reading a spate of poetry and hybrid books by women who were experimenting with voice, the last couple of books I’ve been drawn to (after a couple of weeks of barely reading) have been relatively conventional narratives, both by men, that haven’t rung bells in my soul.

So I know I want one aspect of Marshall’s life—the element of seeking something greater and more fulfilling (or more accurately, I can’t escape it)—but I want Orno’s sense of fulfillment. Can I have both? I think so, but some days it’s really slow going.

Language and Metaphor

Remember when the most stressful question on your English test was, “What is the meaning of the title?” The origins of the title of For Kings and Planets aren’t revealed until about halfway through and then it seems like a casual aside. Orno is writing to Marshall that something or other is named much more conventionally, that it’s not named “for kings and planets.” Actually as I’m typing this, I’m realizing that with Marshall’s love for quoting poetry, it must be a quote, likely from Auden, but I’ll let you seek that on your own (poetry is better in context anyway). What I like about the title, though, is that a whole other dimension of it emerges just in the final pages of the book and in a very subtle way and I started to understand who is orbiting whom.

When this book was published, Canin was teaching at The Iowa Writer’s Workshop and the language is suitably beautiful without being at all show-offy. Still, this is a book where I underlined lines more because I recognized something in the characterization than because of a turn of phrase I loved. Speaking of characterization…

Familiar Characters

If I told you that both Marshall and his professor father—men who are hungry for a greater life which sometimes makes casualties of the people around them—seemed familiar, you might think I was talking about you. Because the truth is that most of the people who read this blog are my friends or family. The other truth is that I’m surrounded by seekers and dreamers. Or rather that I surround myself with seekers and dreamers.

The scary truth is I recognized that “making casualties of the people around you” part as something I’m prone to. It’s something I fight against, when I’m aware of it, but sometimes that hunger to become something greater is all-consuming. All. Consuming.

Why I Can’t Love this Book

And this book isn’t consuming at all. It’s distant, not angst-ridden. It’s psychological when I want it to be emotive. And it never acknowledges the place between dreamer and grounded that most of us make our lives in. Which means the characters ultimately lack nuance.

So many times as I was reading this book as Marshall quits school and runs off to Hollywood to read screenplays all the while showering admiration on his more grounded friend, I wanted Marshall to find some element of satisfaction. I wanted Orno to feel some control over his own destiny. But never the twain shall meet. And the book ends up feeling flat in that way that so much contemporary fiction is criticized for.

I hope I haven’t completely spoiled the book for you. But maybe I’ve saved you a little time, too. Because whether you’re a seeker who longs to be grounded or a salt-of-the-earth type who longs to dream, I think you can push yourself harder than Canin will push you with this book. And I’d love to hear about your struggles and triumphs in the comments.

As for me, I’m off to harvest some plums from our back yard. Maybe somewhere in the manual, mindless tasks of picking, washing, peeling, boiling, and preserving, I’ll find the space to dig into my creative self and wrench out whatever’s standing in my way. Because the grounded self and the seeker self are not mutually exclusive. And my destiny is to try to be both at once, or at least in turns.

Wish me luck…

If you want to decide for yourself, pick up a copy of For Kings and Planets from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

I started reading The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium & Discovery by Amitav Ghosh because I’ll be traveling to India in just over a month. The book had been in my to-read pile for ages and I’d heard good things about it, I just wasn’t ready to read it… until now. And what I found in those pages made me glad I waited to read it, because if I had read this book at any other time, I would have missed what became the central lesson of the book for me: thinking beyond the expected.

I started reading The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium & Discovery by Amitav Ghosh because I’ll be traveling to India in just over a month. The book had been in my to-read pile for ages and I’d heard good things about it, I just wasn’t ready to read it… until now. And what I found in those pages made me glad I waited to read it, because if I had read this book at any other time, I would have missed what became the central lesson of the book for me: thinking beyond the expected. I picked up Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit on a night when I was headed to a gathering of female writers (a group that will not be named). During dinner before the event, Ann Hedreen and I discussed what we really thought of this group. I was wrestling with the fact that the event had to be secret. That the organizers felt they had to exclude men. And that they had named their group after a remark by someone they would consider part of the patriarchy. It all felt so reactive.

I picked up Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit on a night when I was headed to a gathering of female writers (a group that will not be named). During dinner before the event, Ann Hedreen and I discussed what we really thought of this group. I was wrestling with the fact that the event had to be secret. That the organizers felt they had to exclude men. And that they had named their group after a remark by someone they would consider part of the patriarchy. It all felt so reactive. The next book I picked up, When She Named Fire is a collection of poems by women. I have to admit I haven’t gotten very far into the book yet because I was so floored by

The next book I picked up, When She Named Fire is a collection of poems by women. I have to admit I haven’t gotten very far into the book yet because I was so floored by  Courage: Daring Poems for Gutsy Girls was co-edited by

Courage: Daring Poems for Gutsy Girls was co-edited by  The irony of Talking to My Body is that I found author Anna Swir through a collection anthologized by Czesław Miłosz who at every turn celebrated her feminism but in the most misogynistic tone. I can’t really explain and I think it was well intentioned and also cultural. Regardless, after reading one or two of her poems, I had to have more.

The irony of Talking to My Body is that I found author Anna Swir through a collection anthologized by Czesław Miłosz who at every turn celebrated her feminism but in the most misogynistic tone. I can’t really explain and I think it was well intentioned and also cultural. Regardless, after reading one or two of her poems, I had to have more. Awhile back (longer ago than I’m willing to admit), a dear friend, Natasha Oliver, asked me how I find out about new authors. And I didn’t know how to answer her because sometimes it feels like they just materialize from the noise of our digital zeitgeist. But then Icess Fernandez Rojas posted on Facebook this weekend asking for recs of new Latin American authors and I realized it’s time to look deeper into my sources and see where that information really comes from.

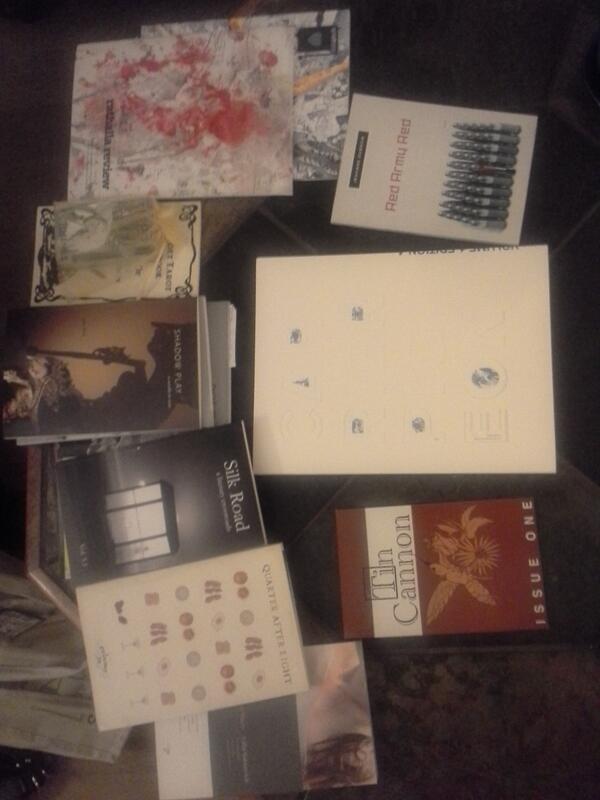

Awhile back (longer ago than I’m willing to admit), a dear friend, Natasha Oliver, asked me how I find out about new authors. And I didn’t know how to answer her because sometimes it feels like they just materialize from the noise of our digital zeitgeist. But then Icess Fernandez Rojas posted on Facebook this weekend asking for recs of new Latin American authors and I realized it’s time to look deeper into my sources and see where that information really comes from. Sometimes the books come to you. There were not a lot of big name publishers at AWP this year, but that made me pay even more attention to the smaller publishers who were there like Ahsahta Press (above) who has some of the prettiest book design in the business. Kim Addonizio’s book called to me off one of the shelves. Actually, enough books called to me to fill my very large coffee table.

Sometimes the books come to you. There were not a lot of big name publishers at AWP this year, but that made me pay even more attention to the smaller publishers who were there like Ahsahta Press (above) who has some of the prettiest book design in the business. Kim Addonizio’s book called to me off one of the shelves. Actually, enough books called to me to fill my very large coffee table.

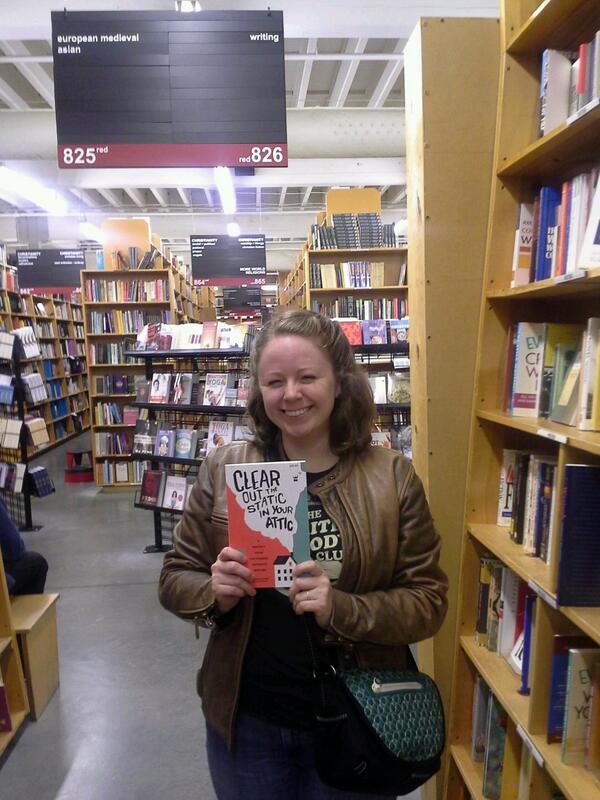

Sometimes a book just jumps off the shelf at you. I rarely go to the bookstore with something in mind. Instead, I try to allow myself a lot of time for the books to call my name. If Serendipity is not responding, try browsing by color or imprint or any other way you don’t normally categorize books. You’ll be surprised by what you discover.

Sometimes a book just jumps off the shelf at you. I rarely go to the bookstore with something in mind. Instead, I try to allow myself a lot of time for the books to call my name. If Serendipity is not responding, try browsing by color or imprint or any other way you don’t normally categorize books. You’ll be surprised by what you discover. I actually never go to the library because I prefer to write all over my books, but librarians are treasure troves of information. These wonderful people have read more books than I’ll ever see and are trained to think about information from a variety of perspectives so they can recommend exactly the right book to you at exactly the right time. When I grow up I want to be Nancy Pearl.

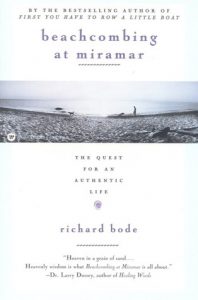

I actually never go to the library because I prefer to write all over my books, but librarians are treasure troves of information. These wonderful people have read more books than I’ll ever see and are trained to think about information from a variety of perspectives so they can recommend exactly the right book to you at exactly the right time. When I grow up I want to be Nancy Pearl. I read Beachcombing at Miramar: The Quest for an Authentic Life by Richard Bode just as I was changing jobs earlier this summer and somewhat terrified that I’d never write again. Things are better now, as of this weekend I have two books started and a jumble of poetry I vow to someday edit, so I feel like I can finally talk about this book and what it means to me.

I read Beachcombing at Miramar: The Quest for an Authentic Life by Richard Bode just as I was changing jobs earlier this summer and somewhat terrified that I’d never write again. Things are better now, as of this weekend I have two books started and a jumble of poetry I vow to someday edit, so I feel like I can finally talk about this book and what it means to me.