Why Book Cover Design Matters

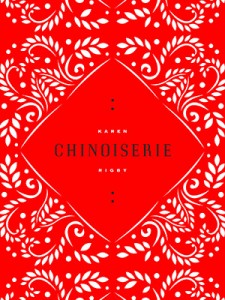

We all judge books by their covers. There is only so much time in the world and there are a lot of books. A lot of time smaller presses don’t have the cash to get great designs or they don’t have someone on staff with a strong eye for design. I don’t know the story behind the cover design for Chinoiserie, but I do know that the organic white shapes against a lush red background is gorgeous. The book feels Asian and yet it’s reminiscent of European toiles and Islamic designs as well. It’s simple and yet it’s transnational. Much like the poetry itself.

This attention to detail continues on the inside of the book with a leaf of vellum before the title page. The title page itself is one of the most attractive I’ve ever seen. It boldly and cleanly declares the title across two facing pages with two lines of Rigby’s poetry, “Dear Reader, what I started to tell you / had something to do with hunger” spanning the bottom of the title. No illustration, just that inviting text.

I don’t usually spend a lot of time talking about the design of books, and I don’t want you to get the idea that the outside is more important or interesting than the inside, but aesthetics do matter. I recently went through this design process with a book of writing prompts I co-authored that’s forthcoming from Write Bloody, another small press. We hated the first design. Actually, it was pretty cool, but it said all the wrong things about our book. I’m glad we spoke openly and honestly with the press. I know the budget is tight, but in just one turnaround, we got a cover that’s inviting instead of scary and I’m really happy with the results.

What’s important is that the book design of Chinoiserie made me want to linger over Rigby’s poetry, so let’s do that now…

A World of Poetry

I knew this was the right book for me when I saw that it was divided in three sections each introduced by an epigraph from a Spanish-speaking poet. Rigby quotes from Pablo Neruda, Federico García Lorca, and Octavio Paz. Epigraphs are amazingly important to a book and I sometimes forget that, skimming over them. But here, Rigby reminds me that it’s not just the words in the epigraph that are important, but the other details as well. Because she chose poets rather than essayists or definitions, I stayed in the poetic sphere of my brain as I was reading. By embedding the epigraphs in the text of the book rather than placing them somewhere before the table of contents, she brought them in closer relation to her own work. And because of who she chose, poets that I personally love, I felt closer to the text–more invested in it.

But this isn’t the only way that Rigby brings the world into her poems. Her subject matter spans the globe. As you might imagine, I love that. She wraps her words around subjects as diverse as Pittsburgh and borscht, as international as the film of The Lover and women harvesting lavender. What could be disjointed instead weaves together into a gorgeous portrait of what it means to observe the world carefully.

Unexpected Imagery

“her body as shorthand / for what his body mistook for love” – Karen Rigby, “The Lover”

One of the things I loved most about this book is the way Rigby uses words to make me look closer at the everyday. It’s something we’re all supposed to do as writers, but it sometimes feels damned hard. But Rigby’s use of phrases like “lizard-dark” make creating that perfect image look easy and I want to know more about that creepy night. When she writes about “a matchbook / missing half its lashes” I know exactly what she means and I wish I could have put those words to the image. And there’s an undercurrent of flirtation there that makes me think of all the phone numbers ever written into matchbooks.

Sometimes these images turn into full-on scenes when Rigby creates phrases like “Places you meet turn semaphore” and I picture both the signalling flags and the metaphor behind it and a story starts to form from those few words. When when she writes about The Lover, “hunger traced the Mekong” I can feel the sensuality in that line and also the geopolitical import. Because Duras is one of my favorites and I’ve watched the film over and over, I remember images of the older Chinese man tracing his fingers over the young, bony, French girl and think of the many forms of hunger.

Rigby makes me want to spend more time digging into my own images and making them this evocative and concise.

The Power of Repetition

I love repetition in its many forms from anaphora to epistrophe. I’ve written about it before and will continue to because of its incantatory magic. What Rigby shows me in “Orange/Pittsburgh” is the power of implied repetition. Let me explain, but first, let me show you. In the third stanza of this poem, Rigby writes, “Orange is girder / & rusted flange, citrine” and then in the middle of the sixth, seventh, and eighth stanzas that “Orange is” returns like this…

“Orange is Japanese carp

beneath the tattoo needle,habaneros sweating

in their grocery bins.

French horns warmingon the south cathedral lawn.”

– Karen Rigby “Orange/Pittsburgh

See how your mind fills in “Orange is” before “habaneros sweating” and again before “French horns warming”? I don’t know if this spell works because I’m so conditioned to rules of three or if including “Orange” in the title is what makes the magic, but I loved the tension between the words I was hearing as I read this poem and the words on the page. It opened a whole new space of reading for me.

Although some of the poems in this collection were too spare for me to get inside, I will return to this book over and over to learn from Rigby’s use of language and to see if they open to me. And I hereby vow not to prejudge literary products from my home state nearly as harshly in the future.