I had the privilege on Thursday night of moderating a discussion between three authors I deeply respect: Micheline Aharonian Marcom, Rebecca Brown, and Elena Georgiou. On the stage at Elliott Bay Books in Seattle, I asked Elena about her recent collection of stories, The Immigrant’s Refrigerator, specifically about how she’d managed to fully explore the humanity of every character in the book. Turns out I lucked into something because she said that was the kernel of what made her write the book, that long ago in her London-centric life the experience she’d had of reading The Song of Solomon and getting so inside the life of an African American family in the faraway U.S. had shown her the power of words to inhabit the experience of another. We need that right now.

I had the privilege on Thursday night of moderating a discussion between three authors I deeply respect: Micheline Aharonian Marcom, Rebecca Brown, and Elena Georgiou. On the stage at Elliott Bay Books in Seattle, I asked Elena about her recent collection of stories, The Immigrant’s Refrigerator, specifically about how she’d managed to fully explore the humanity of every character in the book. Turns out I lucked into something because she said that was the kernel of what made her write the book, that long ago in her London-centric life the experience she’d had of reading The Song of Solomon and getting so inside the life of an African American family in the faraway U.S. had shown her the power of words to inhabit the experience of another. We need that right now.

Here’s why you need to go read The Immigrant’s Refrigerator and then buy a copy for a friend who might not buy one for themselves.

Reading Builds Empathy

You’re a reader. You’ve probably seen the studies that say reading literary fiction builds empathy. If you’re like me, you read a summary of the study, felt good about yourself and went on your reading way. Trouble is that I didn’t really change what I read as a result of those studies. I just kept empathizing more and more with the people I’d already been reading about.

Reading=good. Now let’s take it one step further.

Exposing Ourselves to the Other

I’m proud of the fact that I usually read stories about people who live far away from me. What I’m too often missing in my reading list, though, is stories about people whose life experience is not that of a middle to upper class intellectual-type. I read about countries I’ve visited or lived in that I miss or countries that remind me of them. Occasionally I lament that I don’t read enough about Africa, but I haven’t mended my reading ways.

The Immigrant’s Refrigerator pushed me into reading about all kinds of lives I’d never considered exploring. And I loved every page of it. I picked up the book because I wanted to be prepared for the event at Elliott Bay. What I was not prepared for was entering—on the first page—the life of a man who makes soup for children who are riding atop trains to cross into the U.S. from Mexico and to those who’ve returned. “Gazpacho” is emblematic of the rest of the book in that it’s compact, revolves around food, and drops the reader deep inside the experience of another.

Georgiou does this again and again in the book. From the life of a Northern Irish rent boy in New York City to a Somali refugee who’s terrorized by an intended act of kindness by an employer, to a lonely baker who finds connection and companionship with a refugee from Niger, Georgiou fully realizes the widest range of experiences I think I’ve seen together in one book. But you almost don’t realize how disparate the events that got these characters to their moment on the page are, because rather than playing to any of the expectations we’ve already set about what the other is, the stories in The Immigrant’s Refrigerator focus so deeply on the characters’ human commonalities. This makes it easy to empathize with all of them and the result is as beautiful as the writing.

As easy and pleasurable as The Immigrant’s Refrigerator is to read, it’s not a facile book filled with happy glossy images of what people could be. Some of the stories I ended up loving most were the ones I initially resisted because the characters were too tetchy or far from my own experience (or too close to experiences I’ve tried to leave behind). One of these was “Pork is Love” where a rural Vermonter challenges his Nigerian pastor to preach a sermon about pork fat. Throw those three elements in a story and you could feel very much like you’re in a blender, but with Georgiou’s approach of reaching first for what is human, she finds unexpected light and darkness in both characters and ways of weaving them together that surprised, delighted, and challenged me.

Step Three: Changing the World

Easy peasy, right? Of course not. But if you need a refresh on looking beyond your bubble (and I think we all do right now) take a few hours to sit with The Immigrant’s Refrigerator and remember the things that could bring us together. It’s the only act that can truly put us back on the right path. The challenge I’ve set for myself right now is to look inside of people whose views I disagree vehemently with and try to understand what they most want. Usually it’s things like a better life for themselves and their family, freedom from fear, a genuine moment of feeling seen. I can relate to all of those, and we can build from that.

Acknowledging the humanity of the people around and across from us is a gift we can give them, and it’s a gift we can give to ourselves. It’s the smallest and biggest step toward rebuilding our society and it’s time we take it.

I’m going to go read The Song of Solomon now, you go pick up your copy of The Immigrant’s Refrigerator from Bookshop.org and then recommend this book at your next book club. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission. Bonus points if we change the world along the way.

I’ve been going on and on for about six years about how I don’t know anything about poetry. This repeated admission has been a laying bare of my insecurities and a spur to jump into this abyss I feared so much but could not resist. And in truth, I’ve been writing poetry now, consistently and improvedly, for over three years, but I still hunger to know more and to work through this feeling that there is something I am missing.

I’ve been going on and on for about six years about how I don’t know anything about poetry. This repeated admission has been a laying bare of my insecurities and a spur to jump into this abyss I feared so much but could not resist. And in truth, I’ve been writing poetry now, consistently and improvedly, for over three years, but I still hunger to know more and to work through this feeling that there is something I am missing. Not many people have the fortune to read a biography of their grandfather. I feel especially privileged to have just finished reading Energy: The Life of John J. McKetta Jr. while my beloved grandfather, a man I call Djiedo, is still alive at 102. Written by my cousin, Elisabeth Sharp McKetta, this loving portrait not only brought me closer to my roots, but in doing so helped me find comfort in a time gone awry. It is impossible to impartially review this book, but I do want to share some of the lessons I learned while reading it, because, while some are very personal, I think they can help more than just me.

Not many people have the fortune to read a biography of their grandfather. I feel especially privileged to have just finished reading Energy: The Life of John J. McKetta Jr. while my beloved grandfather, a man I call Djiedo, is still alive at 102. Written by my cousin, Elisabeth Sharp McKetta, this loving portrait not only brought me closer to my roots, but in doing so helped me find comfort in a time gone awry. It is impossible to impartially review this book, but I do want to share some of the lessons I learned while reading it, because, while some are very personal, I think they can help more than just me. A good book opens you—to worlds you would never know, to the experience of being human, to yourself. Daughters of the Air by Anca Szilágyi did just that. This story that touches Argentina’s Dirty War, the gritty days of Brooklyn, and what it’s like to be alone in the world before your time shows, through one family’s experience, how tragedy and political upheaval can upend lives and alter forever the future we once thought we had.

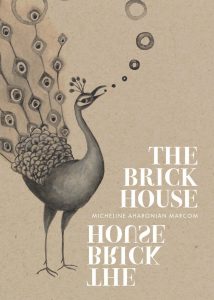

A good book opens you—to worlds you would never know, to the experience of being human, to yourself. Daughters of the Air by Anca Szilágyi did just that. This story that touches Argentina’s Dirty War, the gritty days of Brooklyn, and what it’s like to be alone in the world before your time shows, through one family’s experience, how tragedy and political upheaval can upend lives and alter forever the future we once thought we had. Years ago, when I was still waiting for someone to tell me what it meant to be a writer, I read a panel discussion in Poets & Writers with a group of agents who said you only get one dream per book because dreams are too easy a way to spell out what a character is feeling. The Brick House by Micheline Aharonian Marcom showed me what was really too easy was that quote. By dedicating an entire book to that most revealing condition, she’s shown how complex our dreams, and our lives, really are. My mentor in grad school, I’ve learned a lot from Micheline about how to find my own way as a writer and reading this book showed me not only how far I’ve come but how much farther, still, I can go.

Years ago, when I was still waiting for someone to tell me what it meant to be a writer, I read a panel discussion in Poets & Writers with a group of agents who said you only get one dream per book because dreams are too easy a way to spell out what a character is feeling. The Brick House by Micheline Aharonian Marcom showed me what was really too easy was that quote. By dedicating an entire book to that most revealing condition, she’s shown how complex our dreams, and our lives, really are. My mentor in grad school, I’ve learned a lot from Micheline about how to find my own way as a writer and reading this book showed me not only how far I’ve come but how much farther, still, I can go.