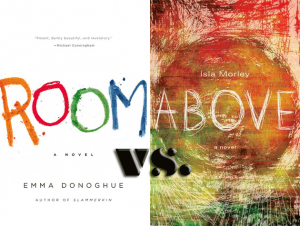

Initially, I was reluctant to read Emma Donoghue’s Room, because I’d recently read Above by Isla Morley and I was pretty sure there were only so many “kidnapped woman imprisoned for years bears the child of her kidnapper/rapist” stories this new mom could take. But I found Room in one of our neighborhood Little Free Libraries and couldn’t resist. As similar as the stories sound at first blush, the books could not be more different. Except that I loved them both.

Initially, I was reluctant to read Emma Donoghue’s Room, because I’d recently read Above by Isla Morley and I was pretty sure there were only so many “kidnapped woman imprisoned for years bears the child of her kidnapper/rapist” stories this new mom could take. But I found Room in one of our neighborhood Little Free Libraries and couldn’t resist. As similar as the stories sound at first blush, the books could not be more different. Except that I loved them both.

Point of View

Above begins with teenaged Blythe’s first-person account of her kidnapper closing the door on her.

“Dobbs wins the fight easily. He shuts and locks the door. I feel a small sense of relief. With a hulking slab of metal separating us, I am finally able to breathe just a little. It is only when I hear another thump, another door closing someplace above me, that I understand: not only am I to be left alone; I am to be hidden.” – Isla Morley, Above

For the rest of the book we are immersed directly in the immediate experience of someone who has been kidnapped. At first, the world of the abandoned missile silo where Blythe is being kept is entirely new to her, and we’re with her as she discovers all the sights and sounds, writes a note to her parents telling them she’s run away, and is about to be raped by Dobbs (that particular action happens mercifully offscreen). The effect of this viewpoint is intense, intimate, and terrifying.

Whereas Room is told entirely from the point of view of Jack, a five-year-old boy who was born in captivity. While Morley is able to show us Blythe’s former life through flashback, Donoghue has created a narrator with no experience of life outside. For Jack, that one room is the entire world.

Writing from the point of view of a kid is a challenging thing to do. Creating an entire world for a reader in a compelling way using this limited voice is even more challenging, but Donoghue nails it. Not only are the cadence of Jack’s speech and his tics well-honed and interesting to read, the way he sees the world is also fascinating.

“I count one hundred cereal and waterfall the milk that’s nearly the same white as the bowls, no splashing, we thank Baby Jesus. I choose Meltedy Spoon with the white all blobby on his handle when he leaned on the pan of boiling pasta by accident. Ma doesn’t like Meltedy Spoon but he’s my favorite because he’s not the same.” – Emma Donoghue, Room

Would you believe I chose that paragraph at random? The entire book is like that with the incredible rush of child’s-view detail in a child’s grammar and mingled with reminiscences of simple moments all managing to reveal insights into the characters. We learn about the tiny room and a day-to-day schedule that feels completely composed of play until nine o’clock when Jack retires to “Wardrobe” and beep-beep Old Nick (their captor) comes to visit Ma.

Sometimes it took me awhile to catch on to what Jack meant by phrases like “I have some now, the right because the left hasn’t much in it” and the book took me much longer than usual to read, but I cherished every minute. I was astounded by how well Donoghue pulled off Jack’s point of view and if I were to re-read this book for anything, I would re-read it for this fantastic voice work.

The Kidnapper

The push-pull relationship between Blythe and Dobbs is the central conflict of life inside the silo in Above. As a result, we get to know the man and his motives relatively well. We learn that believes the world is about to come to an end and that by sequestering Blythe he’s actually saving her from imminent disaster.

For the first half of the book it’s impossible to tell if he’s mentally ill or deeply prescient, but it’s clear that he believes he’s doing the right thing. Which creates a strange but important possibility for sympathy for this character. He’s not a cardboard cutout of pure evil. He has motivations. He means well. This rounded portrait creates an antagonist who’s much more chilling because he’s much more believable and the possibility remains open that he’s saving Blythe’s life.

In Room, the kidnapper—Old Nick—is barely present. This is a really interesting choice because it makes the story almost entirely about Jack and Ma. Donoghue accomplishes this by having Ma almost entirely shield Jack from Old Nick. He knows about the child’s existence, but in their everyday life, the two are never allowed to meet. We learn things about Old Nick entirely from what Ma tells Jack which means that although we can imagine the awfulness of his deeds, our own view of him is somewhat protected. As a result, it’s harder to feel the menace of Old Nick (even though we know by the fact that he’s kept this woman caged in a garden shed that he’s a really bad guy) and the story really focuses on the relationship between Jack and Ma. And Ma is Jack’s antagonist.

The World Outside

Here’s where the spoilers start.

When Blythe finally escapes the silo, she finds the entire world changed. Dobbs may have been a lot of bad things, but it turns out he was right. And he did save Blythe’s life. As she navigates the post-apocalyptic world with Adam, the child she raised and with whom she escaped, we learn how very different the world outside is from Blythe’s childhood memories. It is still a tale of survival, but suddenly the silo seems like a haven stocked with food and free from outsiders. And a new dimension of the story emerges: fertility.

The two halves of Above really do feel like two different books, but they could not exist without each other.

While in Room, Jack the outside doesn’t even feel real. Jack relates it to television because it’s what he has to relate it to. The idea that there are buildings and other people and a whole world out there feels as real to him as his good friend Dora (the Explorer). The conflict of the story hinges on Jack’s desire to stay inside this womb with his mother and her desire to escape. Once they do escape, the conflict shifts to Jack’s desire to return to that womb while Ma wants to live in the world she once knew. One scene I related very personally to is when Jack tries to stop Ma from taking the first shower she’s taken in years.

Maternal Instinct

As a new mother, the hardest parts of Above for me to read were when Blythe’s natural born child dies and then later when Charlie, the child Dobbs brings to fulfill her maternal desires suffers. This is also when Blythe really comes alive as a mother, which was interesting for me to read as my own maternal instincts were peaking out. But what really spoke to my heartstrings was the relationship between Blythe and Adam after they escape. Watching the mutually protective relationship was extra poignant for me as I wondered what my relationship with my son would eventually be like. As I hoped he will have a life that doesn’t require protecting me.

But it was Room that really spoke to the mom in me. The womb metaphor could have been overplayed but wasn’t. I read most of the book as my son played next to me. I wanted to protect Jack like I’d protect my own son. I felt the sweetness and irksomeness of the demands of attention. I wanted Ma to be free of the room as much as I wanted to snuggle that little boy. I loved reading about the way Jack reasoned and imagining what worlds my son will invent as his brain develops. At times I felt Jack’s voice could have been coming from my son. And yes, when he nurses, I sometimes ask him if he “wants some” and wonder if the left or the right is more creamy.

As much as I resisted reading Above and Room, these are both good books. I’d recommend Above for the dystopianists and Room for the moms. But they are even more interesting in tandem.

To do your own comparison, pick up copies of Above and Room from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.