In the The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon weaves together a series of unlikely events using the voice of a compelling narrator to form the story of a postal conspiracy. From the first sentence of the novel as the narrator takes the protagonist Oedipa from Tupperware party to being the executrix of the estate of a real estate mogul, the novel is full of wild and unexpected turns. These turns might be difficult for a reader to navigate if it weren’t for the extraordinary voice of the narrator.

The voice is whimsical and often strays off topic. For example, just after Oedipa hears about her role in the Inverarity will, the narrator muses:

[s]he tried to think back to whether anything unusual had happened around then. Through the rest of the afternoon, through her trip to the market in downtown Kinneret-Among-The-Pines to buy ricotta and listen to Muzak (today she came through the bead-curtained entrance around bar 4 of the Fort Wayne Settecento Ensemble’s variorium recording of the Vivaldi Kazoo Concerto, Boyd Beaver, soloist); then through the sunned gathering of her marjoram and sweet basil from the herb garden” (10).

The reader is given all sorts of extraneous details, but because the details are so interesting and unusual and because the narration always loops back to the topic at hand (in this case, Oedipa thinking about whether anything unusual had happened), I was interested in learning more and was not lost in the narration. I was however carried away by it. The voice of the narrator was like someone telling a story who has so much detail they want to pack in but they are trying to keep in mind the forward thrust of the story. Because the novel becomes a sort of mystery, I wanted to re-read portions of the novel and see if this extraneous information was in fact pertinent or led somewhere. The voice of the narrator was interesting enough to make me think everything he said had meaning and import.

I have read breathless narrators before, the type who are trying to keep up with the pace of the story and the effect is “and then, and then, and then…”, but this narrator was in control of the story and was going to let it unfold at his pace. The effect was intoxicating. Despite the odd character names and the implausibility of the events, I was willing to follow this story through orgiastic sex scenes and nights spent following a bum just to see where on Earth he was going with the story.

It’s an interesting effect to have a narrator who is so in control of what’s happening. Control may be the wrong word, because it doesn’t seem as though he is orchestrating it. Rather it seems as though he alone knows what is going on. This novel would have been a mess with a less omniscient narrator because Oedipa has no idea what is going on. The reader would be immersed in her confusion and would have difficulty following the threads of the mystery. In fact, it is the juxtaposition of this compelling, competent narrator with Oedipa’s confusion that gives the reader the freedom to follow the narrative. It could and does go anywhere, but the coolness of the narrator gives the novel a semblance of order and perhaps even predestination. I wouldn’t go so far as to say the narrator in this novel is God, although narrators can take on a certain deific quality, but the narrator does provide order to the universe of this novel.

I did not use an omniscient narrator in Polska, 1994, but I can see from this novel how important it is for the voice that is doing the storytelling to be compelling. I considered using a cooler retrospective voice for the part of my novel where Magda is leading up to her regrets and then transitioning to in-the-moment narration for the remainder of the book. By starting with the cooler voice, I would like to keep a reader’s confusion to a minimum as she comes to understand the world the way Magda sees it. The retrospective voice would have allowed Magda to draw some conclusions about her life and her experience and to let the reader understand her life through those conclusions. I ended up going with something that was more raw and immediate—something that spoke to her post-rape turmoil.

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of The Crying of Lot 49 from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

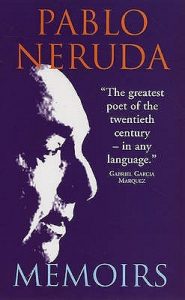

Pablo Neruda had a fascinating life and met all sorts of interesting people from Che Guevara to Federico García Lorca. But in reading his Memoirs, I felt like he was recounting all of these stories to me as opposed to letting me relive them with him. Although Neruda uses some dialogue, he rarely ventures into full-blown scene. The closest he gets are little vignettes like:

Pablo Neruda had a fascinating life and met all sorts of interesting people from Che Guevara to Federico García Lorca. But in reading his Memoirs, I felt like he was recounting all of these stories to me as opposed to letting me relive them with him. Although Neruda uses some dialogue, he rarely ventures into full-blown scene. The closest he gets are little vignettes like: