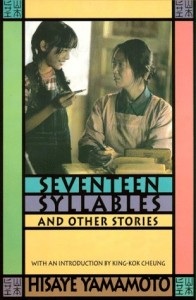

Family tension seethes under the surface of the title story of Hisaye Yamamoto’s story collection Seventeen Syllables. Mrs. Hayashi has given up her passions long ago for a life of quiet suffering. When she discovers an interest in and a talent for haiku, she adds heat to the simmering boil of her family life. And yet Yamamoto conveys the initial familial tension and ensuing boil over through the careful, almost quiet, use of displaced description and contrast.

Family tension seethes under the surface of the title story of Hisaye Yamamoto’s story collection Seventeen Syllables. Mrs. Hayashi has given up her passions long ago for a life of quiet suffering. When she discovers an interest in and a talent for haiku, she adds heat to the simmering boil of her family life. And yet Yamamoto conveys the initial familial tension and ensuing boil over through the careful, almost quiet, use of displaced description and contrast.Description of the family life and Mrs. Hayashi’s character do not take place how I expected. Poetry is Mrs. Hayashi’s one passionate outlet and she reaches out of her placid shell to introduce her daughter, Rosie, to this expression of her soul. When Rosie responds patronizingly to her poem and subsequent description of haiku, Mrs. Hayashi gives no facial expression-only a response which Rosie takes as either satisfaction or resignation. A different writer would fashion a blowup here and the character’s passions would bubble all over the page. By having Mrs. Hayashi retreat into herself, Yamamoto is conveying the depth of her habitual repression.

A similar thing occurs when the Hayashis are visiting the Hayano family. I could feel Mrs. Hayashi brighten when she talked about poetry and the depth of her passion was portrayed only through her distraction from her husband’s needs. I felt already fear for her that she was engaging with Mr. Hayano instead of his wife. Culturally, I expected her husband to bristle at this breach of etiquette. But Yamamoto does not provide a flashpoint here. Instead she shows a wife backpedalling because she knows she’s in trouble, “I’m sorry…You must be tired.” He says nothing and Yamamoto gives only the spare insight of Rosie who “felt a rush of hate for both – for her mother for begging, for her father for denying her mother.” The weight of his control needs no further description.

The sparseness of detail and lack of blowups forced me to read closely, and in reading closer I was able to see where Yamamoto alludes to Mrs. Hayashi’s tension by describing other events. When Rosie is in the bath after her encounter with Jesus, she sings so as not to think of him “the larger her volume, the less she would be able to hear herself think.” She pours on more and more hot water and then immerses herself slowly in the boiling bath “until the water no longer stung and she could move around at will.” Yamamoto is providing a parallel to how Mrs. Hayashi lives her life – she has tried to stop herself from thinking and immersed herself in this heated situation, but she got comfortable and started to move around. Given the controlling nature of her husband, she must at least subconsciously expect to have the heat on the water turned up. So did I. The tension increases, and because the violence of Mr. Hayashi has only vaguely been hinted at, my fear was even greater. Mrs. Hayashi and Rosie know what this man is capable of, but I didn’t and because Mrs. Hayashi is resigned to her fate, I was forced to worry for her.

Yamamoto uses the contrast of the giddy play of the young girls to heighten the effect of the silence of the older women. The girls, even shy Natsu, romp and play and show off Haru’s new coat to the point of barging in on the adults. Mrs. Hayashi shows she wants to be more than the silent, obedient Japanese wife when she engages in the girl’s play, asking to inherit the coat. Mrs. Hayano serves as a cautionary character who, though she spends most of the scene “motionless and unobtrusive,” continues to fulfill her wifely duties in bearing children and fixing tea. This one page explores the full range of female openness within their culture and illustrates how delicately Mrs. Hayashi teeters between childlike bursts of excitement and the expected sobriety of a Japanese wife and mother.

We see from other exchanges that Mrs. Hayashi has not lost all sense of decorum. When Mr. Kuroda comes to deliver her award, her speech is so perfectly written, I could hear the softness of her whispering and the extra syllables she would have added in Japanese to speak in the properly indirect and feminine manner. “It is I who should make some sign of my humble thanks for being permitted to contribute.” Though even here she breaks form by asking to open the package in his presence, a general taboo.

Yamamoto raises tension with the heat, literally. The heat of the day and the imminent tomato spoilage provide atmospheric clues to the coming climax. Everything is hinted at, much like real conversations in Japanese. A character in another story from the same collection explains the culture, “Like a Japanese – quiet.” Yamamoto is softly yelling for me to pay attention. We aren’t privy to the shameful scene in which Mr. Hayashi must surely have thrown Mr. Kuroda out and we aren’t privy to Mrs. Hayashi’s torment as she watches her Hiroshige burn, but we don’t need to be. In the quiet desperation that Yamamoto has built, Mrs. Hayashi’s story and her insistence, “Promise me you will never marry!” say it all. The fire is hotter than ever, but she will re-acclimate herself soon enough, and then she will swim free once more.

Quiet desperation is important in my own writing. My characters often cannot say what they feel most deeply and I struggle to convey the constraints of the world to the reader. I can learn from Yamamoto’s way of “throwing” her tension like a ventriloquist throws his voice. I can also learn from her use of contrast to show the tightness of the constraints.

Though I read this book long ago now, I continue to think about Yamamoto when I realize too late that I am in an untenable situation. I think about this steadily heating bath and how comfortable you can feel before you are boiling. I have a terrible memory for books, but sometimes, when the writing is as strong as Yamamoto’s and when the message is something I need to hear, I carry them with me forever.

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of Seventeen Syllables from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.