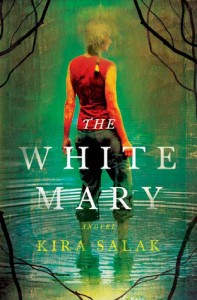

I read The White Mary by Kira Salak on a flight from Seattle to Paris at the start of my first trip abroad in four years. The story of a journalist on a quest for her idol who the world thinks is dead but she thinks might be alive in the deep jungles of Papua New Guinea seemed like an auspicious start to my own (much tamer) adventure: a family trip to Croatia.

I read The White Mary by Kira Salak on a flight from Seattle to Paris at the start of my first trip abroad in four years. The story of a journalist on a quest for her idol who the world thinks is dead but she thinks might be alive in the deep jungles of Papua New Guinea seemed like an auspicious start to my own (much tamer) adventure: a family trip to Croatia.

I used to be a citizen of the world. I’ve visited twenty-four countries, lived on three continents, and can converse in five languages. Except that most of that was before I graduated high school. Though I have done a lot since then to become the person I want to be, I have neglected my wanderlust and let my language skills fester. I had become someone who only travels in the company of a tour director and I became afraid to step outside that bubble.

In contrast, Kira Salak is a travel writer by training and it’s evident in her lush descriptions of foreign people and places. Her protagonist, Marika Vecera, is determined, culturally aware (mostly), and savvy. Things I used to believe about myself. As I read about Marika’s kidnapping in the Congo, I was worrying I wouldn’t be able to communicate well enough to order breakfast. When she was coordinating her trip to the deep interior of Papua New Guinea, I was trying to figure out if I was capable of getting bus tickets from Dubrovnik to Split. I realized how fearful I had become.

The White Mary is engaging overall and I liked reading it. The love story is a little empty—it feels like Salak was as uninvested in it as Vecera was—but I am glad I read this book and even more glad that I passed it along to a fellow traveler.

Croatia, though a fantastic trip, turned out to be much more mundane than the wilds of the South Pacific. I managed to communicate in very basic Serbo-Croatian, German and Slovenian, though most people spoke English. We were never more lost than a missed freeway exit, and I even got to take a train. I was mistaken for a local (my favorite!) once and very briefly. I don’t think I’ll become a travel writer in the near future (unless…), but at least I now remember that the world is full of people, not scary monsters, and I can navigate the globe if I only try.

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of The White Mary from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.