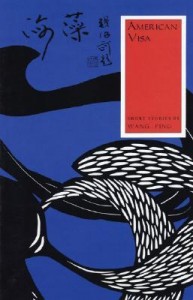

American Visa: Short Stories by Wang Ping covers locations as disparate as the Red Chinese countryside and the New York Subway. The life of her character, Seaweed, is never easy, but the author’s telling of the stories using only the sparest detail removes all trace of melodrama and lets the reader experience it for herself. Using short declarative sentences, Wang lays out the bare facts of the Cultural Revolution, spousal abuse, making it in America as an immigrant, and feeling unloved as a child.

American Visa: Short Stories by Wang Ping covers locations as disparate as the Red Chinese countryside and the New York Subway. The life of her character, Seaweed, is never easy, but the author’s telling of the stories using only the sparest detail removes all trace of melodrama and lets the reader experience it for herself. Using short declarative sentences, Wang lays out the bare facts of the Cultural Revolution, spousal abuse, making it in America as an immigrant, and feeling unloved as a child.

Precise Adjectives

In one paragraph in “Lipstick,” Wang summarizes the barest details the reader needs to know about the Cultural Revolution for the effect of the story. “Who still had the guts to keep a lipstick in 1971, the prime time of the Cultural Revolution? Anything which was related to beauty, whether Western or Oriental, had been banned.” The only adjectives in those two sentences are prime, Western, and Oriental and yet Wang conveys the force of the danger Seaweed was encountering as she explored this forbidden femininity.

Raising the Stakes

“I’d secretly been trading books at school through a well-organized underground network. Everyone obeyed its strict rules: Never betray the person you got the book from; never delay returning books; never re-lend without the owner’s permission.”

Wang identifies the stakes without ever naming the punishment. The reader is dropped into a world of conspiracy and rebellion by school kids and is left to imagine what terrible fate would befall the students if they were caught.

Similarly, she goes from describing Seaweed’s pinching to their mother’s reaction “My mother always punished me with the bamboo stick behind the door.” She fills in the sisterly rivalry, but leads the mother’s punishment up to the imagination.

Always Leave Them Wanting More

Perhaps it is growing up with movies and television, but I am used to having all the blood and guts played out for me. A severed foot is a gross-out tool, but it doesn’t serve a greater purpose. By not telling me what the soldiers would do or what her mother would do with that bamboo stick, Wang has captured my imagination, and the imagination is often much more brutal than what the writer would have described.

Wang doesn’t shy away from bad things, only awful, and that makes my interpretation of the awful even worse. “The Story of Ju” opens “Ju hung herself on the eve of her wedding.” Obviously this is not going to be a happy story, but the simplicity of the sentence shaped my view of the world Seaweed lives in, a world where sadness is quotidian and characters are resigned to their fates, where “the dead are dead.” Even in describing the abuse Ju’s mother, Crazy Hua, suffers, Wang gives us the aftermath rather than the event. “After that, she came to work every day, often starved and badly bruised.” There is no hope that Hua will ever escape her circumstances but Wang is not elaborating on the horrors of their lives with grisly detail, she simply names them.

It isn’t until Wang lets Ju speak for herself that the reader is privy to the events themselves. Even then, as Ju describes her mother kneeling “on the broken pieces of the bowl.” or her stepfather demanding she “replace” her mother as she’s tied to a chair, Wang had so prepared me to imagine my own horrors that the scene came alive in gruesome detail, but only in my imagination. In reflecting on the story, I find it has taken on a new life in my imagination and in fact I remember the details I created as though they were actually written into the story.

Tight Sentences

Although Wang is writing in a second language, there is no accent or accident in her sentences. The entire flavor of Seaweed’s relationship with her sister Sea Cloud is contained in the two sentences that start “American Visa.”

“Sea Cloud asked me to help her get out of China on the night when we were sailing from Shanghai to Dinghai to attend Father’s funeral. I was surprised as well as pleased.”

If this story stood alone, the reader would know from these two sentences that Seaweed is the stronger sister who has managed to escape circumstance and therefore has power in the relationship, but that Seaweed doesn’t know it. Seaweed craves the acceptance of her sister, whom she envies. We also see that it was difficult for Sea Cloud to come down from her perceived pedestal and ask her sister for something, she had to wait for a moment of quiet during a time that would have brought them closer in sharing grief for their father. Two short sentences, almost entirely devoid of adjectives, and Wang manages to convey a lifetime of struggle between two sisters.

In Polska, 1994, I wrestled with how to describe a rape scene and a culture that is foreign to my audience. I wanted the reader to feel the full force of the scene because it causes the transformation in the main character, but I wasn’t sure how graphically I want to lay it out. Wang showed me to use description of horrors carefully. I don’t want to bowl the reader over, I want to provide them the tools to bowl themselves over.

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of American Visa from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.