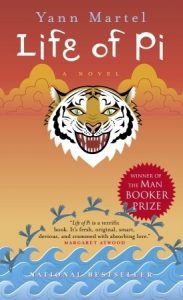

I’m pretty sure I’m the last person on the planet to read Life of Pi by Yann Martel, but if I’m wrong and you haven’t yet read it, skip this review until you have. It will be full of spoilers and I hate to ruin good books. What impressed me most about this book was Martel’s ability to maintain tension in a novel that is literally lost at sea.

I’m pretty sure I’m the last person on the planet to read Life of Pi by Yann Martel, but if I’m wrong and you haven’t yet read it, skip this review until you have. It will be full of spoilers and I hate to ruin good books. What impressed me most about this book was Martel’s ability to maintain tension in a novel that is literally lost at sea.

Introduction

I stayed away from this book for a long time because I like to read books on my own terms without any hype or intervention. And when people would tell me, “It’s this amazing book about a boy on a lifeboat with a tiger, but it’s really about God,” I thought it sounded weird but kept the name for future reference. When the Ang Lee film came out, I could see that it was going to be beautiful and knew I had to see it on the big screen (which meant being subject to Hollywood’s schedule). The movie was stunning and I’m not sorry I saw it, but I also think seeing it before reading the book robbed me of some of the book’s brilliance. I picked up the book this week because I wanted a story, something I could rely on.

Let’s talk about that paragraph I just wrote. It’s long, ambling. It covers a lot of time but doesn’t really have a center. The ideas are there, but it’s not tight and it could definitely be edited down. I bet you even skimmed part of it. I would have. In contrast, Martel’s intro to Life of Pi is tight. The first 50 pages of the book cover all the backstory of an Indian family with a zoo who is moving the zoo animals and themselves to the Western Hemisphere. It covers the story of a boy’s life and his experience as a religious omnivore. It even has an essay on the relationship between animals and humans. But it’s not messy, it’s enthralling.

So how does Martel do it? How does he keep the reader’s interest as he lays all this groundwork. I think it’s precisely the messiness that is so fascinating. But he does have an organizing principle–he uses the author’s introduction to frame for us that this is a story that will make us believe in God (a pretty encompassing idea anyway) and then he lets Pi Patel speak. And it’s no accident that the authorial interjections are more frequent at the beginning, he’s still framing the story for us and interpreting what these divergent threads might someday form, but once we’re hooked, he lets us hear directly from Pi.

Promising a Happy Ending

Would you read a book about a boy who has lost his entire family adrift on the ocean and in mortal danger every minute of every day? I wouldn’t. And I love depressing books. Page after page you’d have no idea if he’s going to get saved or not and eventually your hope would wear thin. You might abandon it before the boy gets saved or eaten.

So why do we read and love this book? Why do we recommend it to friends? Martel very smartly controlled the emotional stakes of the story. We know from the beginning that Pi survives. We don’t know how and we’re still curious as hell about this tiger thing, but we are free to hope. The most ingenious part of this emotional buoying for me was how just before we actually see Pi get lost at sea, Martel describes his family today, and then he writes, “This story has a happy ending.” Wow.

Would I suggest you do this with any other book? Absolutely not. But in a story where despair could be truly overwhelming, it was a genius move.

Keeping the Tension at Sea

Pi is adrift for a very long time. That’s another tricky proposition for a writer. How on earth do you keep readers engaged in what must be the most mind-numbing of days? Here Martel divides up the experience into little sections and each is tightly wound around one idea. There is the quest to get fish and observations of birds. He includes descriptions of distilling and collecting water and other essential knowledge for survival at sea. Oh, and there’s the tiger, Richard Parker.

Richard Parker is essential to maintaining tension out at sea, but even that could get dull for a reader over time. What was interesting for me was how Martel shifted the relationship between Pi and the animals. We get to experience with him the initial uncertainty, the pervasive fear, and the eventual reigning and caretaking. But even when Richard Parker is “tamed,” he’s still a wild animal capable of anything, and Martel doesn’t let us forget that either. All it takes is one swipe of that large claw to refocus our innate survival instincts.

But it’s About God?

What I did lose on the ocean in the book that I did not lose in the movie was the sense of God. At the end I do prefer the allegory to the events retold with human players. But I missed the direct connection with religions that Pi had been experiencing early in the book. And maybe the point is that God is everything and we can’t filter God through a religion. Maybe I need to think about it some more.

I’ve heard told that you know you are done editing a book when you run through one draft and add in commas and on the next draft you’re taking them back out. Life of Pi is that tightly edited and I loved that about it. In some ways the organization of a book that can have exactly 100, naturally segmented chapters with nothing missing and nothing superfluous makes me believe in perfection, order, and destiny. And maybe that’s the part of God I’m looking for right now.

If you still haven’t read Life of Pi, pick up a copy from Bookshop.org. Then read it when you are ready for it. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.