I’d already given up on being a writer when I entered the University of Washington as an undergrad. There was something about deconstructing a text (which is all I thought English majors could do) that made me worry I’d learn to hate reading (the one thing that sustained me always) forever. But I was still a maker. And I needed to put that energy somewhere, so I became a sculpture major. I fucking loved it. Until I stopped.

Asking the Important Questions

I don’t think about drawing, painting, and sculpting much these days, but while wandering the Seattle Art Fair yesterday my artist husband gently nudged open the wound I didn’t want to acknowledge was there. It started with him mentioning that I never draw anymore, talking about how much he liked my drawing, then hinting that some people make work for the very sake of making (a revolutionary concept amidst what felt like the den of art as commerce), and as I shared with him how much I loved just the process of playing with materials, I could feel my hands making the gestures I used to make when sculpting things from clay. I showed him the part of his hip that I had shaped over and over again in object after object and we talked about how much I like textures and which ones.

Why I Stopped

Eventually we got around to talking about what made me stop. See I never cared about the end result. I could shape clay and plaster all day long. I could run a brush or my hands through thick, goopy paint. I could build furnaces and melt metal. I could do anything except finish a project. Because I didn’t care about finishing a project. I cared about the process of making it and the more I worked with the materials, the more I wanted to stay inside that world forever.

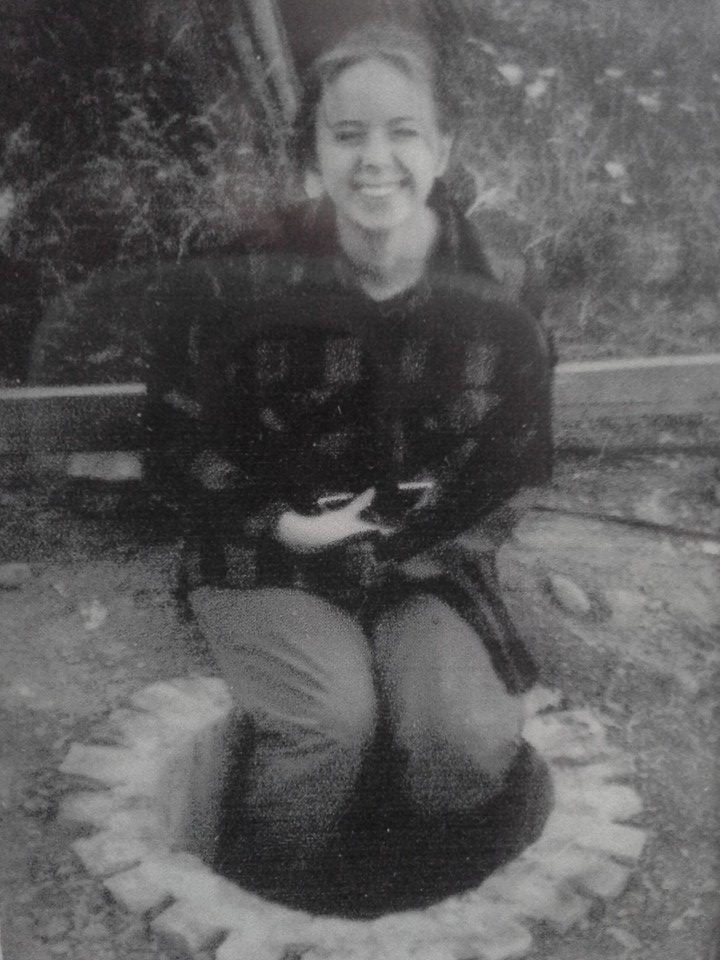

This is the photo I post of myself when I want to impress people. Because it is one of the times in my life I was most impressed with myself.

I organized other artists as the “cupola captain” as we melted iron in 100+ degree weather, and one of them got burned with molten metal because I wasn’t good enough, but it was okay because none of us knew what we were doing and we loved it. I gave constructive feedback and thrived off of the ideas and creative energy of those around me.

But we got to the end of the semester and I had no work to present. I had melted it all back down. And my professor suggested I go back up on the hill and try painting for a while. Which I understood, but which also broke my heart. So when scheduling art classes got hard the next quarter (and the university gently suggested I had more than enough credits to graduate already) I switched back to the sociology and political science degrees I’d nearly completed and got ‘er done.

I never made sculpture again.

The First Time I Quit

This wasn’t the first time my love for visual art had been thwarted. In the eighth grade I’d made a scratchboard picture of a KKK rally that was really good. A fellow student pulled it down off the board and tore it up. In the ensuing school meetings, he stressed that he’d been offended by the work (understandable) but (as much as I believe good art has every right to offend) offense had never been my point. I thought the image of white-clad men around a huge bonfire in the dark was beautiful. I knew the KKK was abhorrent and I never intended to celebrate them, but by making the work I felt like I was coming to understand something about humanity that I could not explain. I didn’t have the words then to explain any of my artistic intentions either or the ways art can and should be myriad, but I could walk away. And I did. In high school I tried art again and made some work that was meaningful to me, but nothing that pushed me (or anyone else for that matter).

About Ursula von Rydingsvard

One of the first things we saw at the Seattle Art Fair that I really connected with was a sculpture by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Better yet, Galerie Lelong also had some of her drawings—charcoal works on paper that she’d woven maroon textiles through and sewn roughly with black thread. I’ve seen (and loved) Ursula’s pieces all over the US, but this work on paper was new to me and spoke to a project that I’d been working on when my grandmother died so many years ago.

I’d read that some number of thousands of people had died in Africa from a preventable disease and I wanted to know what that many lives felt like in my body, so I made a painting and crisscrossed it with monofilament onto which I began tying French knots in red string. Because I lied earlier—I do still think about drawing, painting, and sculpting, and this was the first thing that had compelled me back to work. Each time I pierced the canvas to start a new knot it felt violent (and caused me physical pain because I’m not always careful about how I work). I never finished the piece (I’d rushed the underlying painting and it was bad) but I did feel what I’d needed to feel.

Through all the times my husband and I wandered in and out of the booths in the fair, he had been trying to tell me that more artists than I knew (if they could admit it) were really making their work for that feeling they had while creating. And that Ursula was unabashed in celebrating and focusing on her love for the materials.

When he said that, I felt the kind of opening in my body that you should always pay attention to—weepy grateful and like my limbs were limbering to work again.

(This is how much I love Ursula… I stalk her sculptures wherever I go.)

Will I Ever be a Famous Sculptor?

Unlikely. I love writing and I’ve gone far enough down this path of specialization that my visual art muscles are desperately rusty. I might polish them off again someday, but right now I’m lucky to have a few hours a week to work creatively. Still I can see now how important visual art is to my creative self and that I’ve been missing it. I never really stopped making (because I use that same generative energy in writing, gardening, baking, and making and raising a child), but I better understand the ache I’ve felt in the early mornings when I try to capture the shape of my son’s cheek in crayon on newsprint before he moves… again.

And though I’ll forever be 30 credits short of a degree in sculpture, the ways I learned to think about form, negative space, and the importance of the marks makers leave on their work inform everything I create for myself and for others. I’ve also learned to be myriad and expressive, to be comfortable provoking (at least sometimes).

I can’t promise that I won’t stop making visual art again. But I can say that I won’t be so quick to forget its importance to the writing I do and the person I am. Thank you, Ursula, for being you, and Clayton, for keeping art in my life and yours.

If art is important to your process, I recommend visiting the Seattle Art Fair this weekend. There’s a lot of commerce, a lot of pretense, and also a lot of art. You might just find what you need, too.