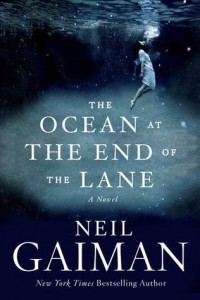

The first night my husband read me a chapter from The Ocean at the End of the Lane by lamplight as I nursed our son, I was certain the story was more than made up. As the narrator returns to his childhood home, I could feel Neil Gaiman flashing glimpses of his childhood into the story. Something about smudging the line between truth and fiction made the book even more of a joy to read (and to listen to) as we followed the fantastic journey of a man reliving a few magical and terrible days in his childhood.

The first night my husband read me a chapter from The Ocean at the End of the Lane by lamplight as I nursed our son, I was certain the story was more than made up. As the narrator returns to his childhood home, I could feel Neil Gaiman flashing glimpses of his childhood into the story. Something about smudging the line between truth and fiction made the book even more of a joy to read (and to listen to) as we followed the fantastic journey of a man reliving a few magical and terrible days in his childhood.

Metafictional Clues

The dedication was my first clue that this book was not as fictional as we usually consider fiction to be. Gaiman writes, “For Amanda, who wanted to know.” I could just picture his wife asking him about his childhood one night and Gaiman spinning this elaborate tale. The epigraph, from Maurice Sendak, deepens the impression that we’re reading a somewhat true story. It reads, “I remember my own childhood vividly… I knew terrible things. But I knew I mustn’t let adults know I knew them. It would scare them.” That epigraph also happens to capture perfectly the feeling of this entire book.

The story begins with a man (unnamed) returning to a half-remembered English hometown for a funeral. There is something so hauntingly true as Gaiman writes about answering the standard questions asked by people who knew you once. They ask about your “work (doing fine, thank you, I would say, never know how to talk about what I do. If I could talk about it, I would not have to do it. I make art, sometimes I make true art, and sometimes it fills the empty places in my life. Some of them. Not all).” Although Gaiman never specifies what type of art the narrator makes, I felt like he was opening his soul in those lines and that coupled with the biographical similarities meant that for me the narrator could not have been anyone else but Gaiman from there on out.

In the end it’s not at all unusual for writers to put themselves in their work whether it’s gathering small observations from their daily lives, mining emotions they have felt, or drawing on actual events. But I was delighted to hear in the acknowledgements, “The family in this book is not my own family, who have been gracious in letting me plunder the landscape of my own childhood and watched as I liberally reshaped those places into a story.”

While metafiction is often defined as a work that brings attention to that work’s status as an artifact, in this case the metafictional elements were subtle enough that they made the story feel more like real life. If you’re familiar with Gaiman’s love of the fantastic, you know what a wonderful feat this is.

Shimmering Truth

The line between fiction and truth isn’t the only one Gaiman dances in The Ocean at the End of the Lane. He also plays with the way memory affects truth. This starts with how memories start to unfold on the narrator as he drives to where his childhood home once stood. The story opens up and we meet a wonderful cast of characters including his childhood friend, Lettie Hempstock, who isn’t as young as she may seem.

I absolutely will not spoil the story for you here, but it’s interesting to note both the way certain memories and events are (almost literally) snipped out of the narrative and the way the narrator’s recollections shift (especially as the story comes to a close). Even the characters change shape between the narrator’s youthful and adult interpretations of them.

As old Mrs. Hempstock says, “Didn’t I just say you’ll never get any two people to remember anything the same?” Sometimes those two people are who we were then and who we are now and I’ve never seen a book capture that difference more perfectly.

Reading Aloud

Ever since my dad read my brother and me the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy, I’ve loved being read to, but it’s an act that takes a lot of dedication on the part of a reader—especially when you’re dealing with novel-length works. For example, I’ve been reading Jo Nesbo’s The Snowman to my husband since April of 2013 and we started The Arabian Nights way back in 2011. So when my husband settled cross-legged on the floor of the darkened nursery and unfolded the case for his Kindle, I scarcely dared to hope that reading was on his mind. And I never thought we’d finish the whole book in under two months.

Being read to is a different (and not always positive) experience. For one thing, I couldn’t picture the names of the characters which made them seem more ephemeral to me. I also found that by not seeing the words of the text I had more trouble recalling what happened the time before.

But the upsides were so amazingly wonderful that I’m already begging my husband for the next book (and may even finish reading those other books to him someday). For one thing, that ephemeral feeling that came with not having seen the words on the page worked for this book. Because I wasn’t turning pages, I felt like I was being told the story by the person who experienced it. Secondly, because we were experiencing the book together, we’d sit after each chapter and talk through what just happened. He was reading the book for the second time and was loving seeing it new through my eyes and I was loving digging for hints and clues about what was to come.

And then there’s the experience of being read to. Each night that my husband sat on that floor I felt so surrounded by love. I can’t wait until we can share that experience with our son (in any way that we think he might remember it). For now, as I finish off the brutal mystery of The Snowman I’ll just be grateful that we can read as adult of material as we please for a few more months.

It turns out that Gaiman read The Ocean at the End of the Lane aloud to his wife each night as he was writing it. Some stories just come alive that way. We’re still looking for the perfect next book to read aloud. If you have any recommendations, I’ll gladly take them.

If you want to embark on an adventure with a Gaiman-like boy and the Hempstock family, pick up a copy of The Ocean at the End of the Lane from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

Though I’m obsessed with philosophy, we have a tortured relationship. The whole concept of discussing an idea and its implications to death is pure heaven for me. But I like to be right (i.e. not WRONG) and I usually feel inadequately prepared to properly discuss important ideas. In reading Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre, there were ideas I wanted to share with friends, but I felt like I couldn’t without going to Wikipedia and determining first that I hadn’t misread the book.

Though I’m obsessed with philosophy, we have a tortured relationship. The whole concept of discussing an idea and its implications to death is pure heaven for me. But I like to be right (i.e. not WRONG) and I usually feel inadequately prepared to properly discuss important ideas. In reading Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre, there were ideas I wanted to share with friends, but I felt like I couldn’t without going to Wikipedia and determining first that I hadn’t misread the book.