I just updated my Goodreads for the first time since early May and realized that in a time of what feels like not-reading, I’ve been reading a lot. Not the volumes of fictions or poetry I’d usually be immersed in, though some of those. I’ve been immersed in all things political. Some of that, like When the Emperor Was Divine, was fiction, and some of it, like James Comey’s statement to the Senate, I can only wish was fiction. Still, it’s been an interesting mix of media and I thought maybe it was time, after three months of not writing a book review, I reflect on what I’ve been reading.

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

Of all the things that have happened in the months since Trump was inaugurated, none has hit me as hard as the Muslim ban. A lot of things have upset me, but that one struck at my core values. For days after it was announced that America was no longer going to be the land of opportunity for all but instead was going to start openly turning away legitimate immigrants en masse, I was glued to the news and Twitter just waiting to see if we’d come to our senses. I was so tuned into events that I tuned out of my family and simply waited.

Of all the things that have happened in the months since Trump was inaugurated, none has hit me as hard as the Muslim ban. A lot of things have upset me, but that one struck at my core values. For days after it was announced that America was no longer going to be the land of opportunity for all but instead was going to start openly turning away legitimate immigrants en masse, I was glued to the news and Twitter just waiting to see if we’d come to our senses. I was so tuned into events that I tuned out of my family and simply waited.

I know the whole land of opportunity thing is a story we tell ourselves just like we tell ourselves that those opportunities are open to everyone. Until that day, though, the story was intoxicating enough that I believed it. I believed we all valued it and were working toward it, even as we struggle with our own racism and anti-immigrant swells.

I don’t know whether When the Emperor Was Divine was sitting in my to-read pile or if I purchased it then or found it at the Little Free Library. I do know that I needed this book this year. Julie Otsuka’s story of a Japanese family living in California then interned during World War II made me look straight into what our country does, not what we say. It made me look at the people we do it to.

The book opens with a Japanese woman, a mother, we later learn, seeing the evacuation order near her home in Berkeley. She returns home and begins packing and preparing her home. Her acceptance seemed strange to me until I understood that her husband had already been arrested. She takes down their artwork, hides their valuables, feeds the stray dog her children cared for a feast and then kills it. When she killed that dog I understood a lot more about her character. This was not a woman who had given up. This was a woman who had no choice and she was going to do the best she could to help her family survive. She knew that dog could not survive alone on the streets and so she gave him the best ending she could. There are glimpses of neighbors helping her in small ways as there are glimpses of the racism her family encounters. But no one can change anything.

Spanning the entirety of the family’s internment and until they and then their patriarch return home, this book is filled with quiet details that speak loud. Otsuka lets us peek inside the experiences of each family member and we see not just the freezing cold, flu and diarrhea of the camps but also a boy’s ritual probing of his imprisoned father’s shoes, the missing of plums, and the worry of whether the porch light was left on or off. We see the family’s strength, their endurance. When the family returns to their wrecked home and works to clean and rebuild it room by room, we think it might be okay, this awful thing that our country did, because they were strong enough to withstand it. But of course it isn’t okay, not that it happened, not that it could happen again. We see this in the father, once a gentle man now broken. All because he had the wrong blood.

As a mother, I admired how well the mother took care of her family even as I ached at how she had to. As a patriot I was disgusted that we ever let this happen. That it could happen again. Sometimes, maybe even most times, we are better at conquering our fear and uncertainty and at becoming the welcoming country I grew up believing in. For example, I’m very proud to be living in one of the first states to push against Trump’s travel bans. But Otsuka reminded me that this impulse to give in to fear is something we have to fight every day or it will bubble right up in the most horrible ways.

Poetry, June 2017

Speaking of people we don’t treat all that well, I’m glad we’re finally having more concerted discussions about race. We need to do more. I’ve spent a lot of time lately thinking about my own racism, but I have much to learn to become the person I want to be— to appreciate the beautiful array of people and experiences in the world. I was delighted, then, when the June 2017 issue of Poetry arrived in my mailbox and it was a tribute to Gwendolyn Brooks. More importantly, it was filled with voices and experiences I don’t always encounter on my own.

Speaking of people we don’t treat all that well, I’m glad we’re finally having more concerted discussions about race. We need to do more. I’ve spent a lot of time lately thinking about my own racism, but I have much to learn to become the person I want to be— to appreciate the beautiful array of people and experiences in the world. I was delighted, then, when the June 2017 issue of Poetry arrived in my mailbox and it was a tribute to Gwendolyn Brooks. More importantly, it was filled with voices and experiences I don’t always encounter on my own.

I’ve read Patricia Smith and even seen her speak, but images like “our someday plans / grayed and siphoned flat” and “drown your baby in the mama-eye” reminded me that I haven’t read nearly enough Patricia Smith. CM Burroughs looks into the hypocrisy and humanity of us all by imagining the strong Brooks as lover with “how many times did / you posture yourself for the broad body of him or him and open // like home” and then shows me by her use of forward slashes that I know nothing about experimenting with language. Reading Roger Reeves I discover that the King Shabazz character in my son’s favorite book is actually named after Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Jacqueline Jones Lamon’s line “I take a sip of water and tell them / every true thing that I know — that they are // the power who will save what needs saving” is everything.

Though I always enjoy reading Poetry, this is an especially fine issue and it’s expanded my reading list in all the right ways.

Walks with Walser by Carl Seelig

One of the most reassuring and also unnerving things about Walks with Walser, the book I’m currently reading, is seeing that art can both endure terrible times but that it can also remove itself completely from life. Chronicling conversations during the 27 years Robert Walser spent in an asylum after a breakdown, this book spans World War II and yet, because it occurs in Switzerland, barely even acknowledges what’s happening next door. There are some really gorgeous reflections on the life of an artist in this book, but it’s also an important reminder to me that I am not content to check out on the real world. Though I could benefit from a few more long walks.

One of the most reassuring and also unnerving things about Walks with Walser, the book I’m currently reading, is seeing that art can both endure terrible times but that it can also remove itself completely from life. Chronicling conversations during the 27 years Robert Walser spent in an asylum after a breakdown, this book spans World War II and yet, because it occurs in Switzerland, barely even acknowledges what’s happening next door. There are some really gorgeous reflections on the life of an artist in this book, but it’s also an important reminder to me that I am not content to check out on the real world. Though I could benefit from a few more long walks.

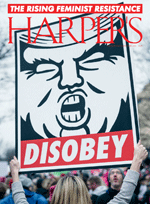

Harper’s

A former student of political science, I’ve long subscribed to Harper’s to keep my political muscle active. It’s been an important lifeline since the election. I’m not one of those liberals who was completely surprised Trump won, I think the Democratic Party ignored the growing dissatisfaction of lower-income and blue collar Americans. But I am appalled that Trump was elected.

A former student of political science, I’ve long subscribed to Harper’s to keep my political muscle active. It’s been an important lifeline since the election. I’m not one of those liberals who was completely surprised Trump won, I think the Democratic Party ignored the growing dissatisfaction of lower-income and blue collar Americans. But I am appalled that Trump was elected.

“Commitment to anything larger than your own life… [is] messy and chaotic and imperfect—which isn’t the flaw of it but the glory of it.” – Leslie Jamison

Though I chose not to attend the Women’s March, a thoughtful and moving essay by Leslie Jamison allowed me to experience the day and also her gorgeous reflection on the lifelong activism of her mother and to understand my own role in making a difference. In the same issue, I learned about an underground movement of ordinary women that had helped women get abortions. and read an excerpt of an essay by Mary Gaitskill that helped me understand how I can raise a son who sees “that rape is a violation of his own masculine dignity as well as a violation of the raped woman.” And I saw a revealing photo essay on what life is like in the projects now, not in some memory of the bad 80’s.

“At it’s best, [feminism] has also been about women recognizing the shifting contours of their own ignorance, and trying to listen harder.” – Leslie Jamison

That was all one issue. I’ve also been catching up on back issues with articles warning of things to come that, by the time the issue’s gone to print, or at least by the time I’ve read it, have already happened. The prescience is reassuring. It makes me believe that although I may feel like the bottom is dropping out, I am not living in unpredictable chaos and if we all think just a little harder and more clearly, we can make the nation as great (in the cooperative, generous, open, humanistic way) as I believe it can be.

Comey’s Statement

One step toward becoming that nation is understanding what’s happening now. I listened to the entirety of Comey’s Senate testimony on Thursday. This time I at least sat with my family while dwelling on current events. Though I hesitate to trust the straightforward earnestness Comey seems to present in that testimony and in his written statement, he made an excellent point about credibility being tied to consistency and Comey is consistent while Trump…

I don’t know what my role is right now in this messy time, but I can bear witness. So can you. If half of what Comey says is true, and I believe much more than that is, Comey is telling us that we have a president who is willing to lie and squeeze his employees and the values our government is founded on to get his way. That should not be a surprise. But it’s time we did something about it.

The Assault by Reinaldo Arenas

I thought I was escaping back into fiction when I pulled The Assault off my bookshelf. I remembered Arenas’ languid, gorgeous language and I really needed a little kick to get back to writing. But of course this Cuban-born novelist who was persecuted by his government is famous for writing about that experience.

I thought I was escaping back into fiction when I pulled The Assault off my bookshelf. I remembered Arenas’ languid, gorgeous language and I really needed a little kick to get back to writing. But of course this Cuban-born novelist who was persecuted by his government is famous for writing about that experience.

This book truly is gorgeous. It’s also a terrifying reminder of what happens when democracy fails. The story of a government agent’s search for his mother so he can kill her before he becomes her, this book shows a country where humanity is reduced to means of production. For example, in one chapter we see the line of people who irrigate the fields with their spit. If they fail to spit, they get juiced and that juice is then used for irrigation. Wild and dark, nothing about the not-night portrayed in this book is wholly implausible. That’s the worst part.

West of Here by Jonathan Evison

West of Here is not a dystopian book. That might be why I sandwiched it somewhere in the middle of all this heavy reading. In fact, it contains elements of the utopias white people wrote about in the 19th and early 20th centuries as explorers went off to conquer new lands and found paradisaical locales with unlimited natural resources. It also contains stories of the people who were already here and a view into what life is like in those same paradises 100 years later. I love reading Jonathan Evison’s descriptions of places I love. I love his understanding of the simplicity and complexity of human motivations. And I love that a strange mystical vein runs through the story. Dams go up, dams come down. People settle, people perish, people endure.

West of Here is not a dystopian book. That might be why I sandwiched it somewhere in the middle of all this heavy reading. In fact, it contains elements of the utopias white people wrote about in the 19th and early 20th centuries as explorers went off to conquer new lands and found paradisaical locales with unlimited natural resources. It also contains stories of the people who were already here and a view into what life is like in those same paradises 100 years later. I love reading Jonathan Evison’s descriptions of places I love. I love his understanding of the simplicity and complexity of human motivations. And I love that a strange mystical vein runs through the story. Dams go up, dams come down. People settle, people perish, people endure.

This is not a dystopian book, but it is a good reminder that while our goals may seem simple, reality is not.

Not everything here counts toward my Goodreads reading goal, and I still don’t have the answers to making this country the place I dream it might be. But the somewhat odd selection does reflect the writer and the human that I am, and I’m choosing to embrace that. For better or worse, I’m going to take a little hope from Evison, a little inspiration from Comey, doses of reality from Jamison, strength from Otsuka, seeing from Poetry, and a prod of fear from Arenas and try to live my own values. I hope I can be at least a little part of the power who will save what needs saving.

And now that I’ve put that vow in print, I can finally clear this stack off my desk.

Leave a Reply