Maybe the reason you can’t go home again is that you can never see all of what it was—you could only glimpse one angle of it and as you age you see another and then another, but the place you grew up and the people you grew up with are amalgams of all the ways you see them over time. That’s how I felt when reading The Grass Harp by Truman Capote before, during, and after a trip to my hometown, Moscow, Idaho.

Maybe the reason you can’t go home again is that you can never see all of what it was—you could only glimpse one angle of it and as you age you see another and then another, but the place you grew up and the people you grew up with are amalgams of all the ways you see them over time. That’s how I felt when reading The Grass Harp by Truman Capote before, during, and after a trip to my hometown, Moscow, Idaho.

How the Fates Wanted Me to Read Capote

My bedside table right now is stacked with thick books that are “good for me” so I’m lucky if I read ten pages a night. Which is frustrating for someone who likes to read a book in a sitting. One night I couldn’t take it anymore and went crawling through my to-read stacks for something slender, something enriching that wouldn’t be so hard. Toward the top of one of the middle stacks, I found this aged paperback, a book I like to believe was once part of my grandmother’s library, and I took it to bed. The novella and stories made for a slow read and I didn’t care because I loved every word.

The other reason I was fitful when I picked up this book was that it was just a few days before I was going home to Idaho for the first time in over five years. It was complicated. My mother and I hadn’t spoken for months because of something she’d said, but I knew I was long overdue on a visit. As Capote’s story unfolded, I saw some familiar characters. Verena was wealthy and in charge, but “the earning of it had not made her an easy woman.” Although Dolly “folded like the petals of a shy-lady fern,” it is her strength that ultimately leads to Collin, Catherine, Dolly to move into a tree. Still hiding in the branches of my own tree, I could empathize with Dolly.

The book is full of amazing (and true-to-life) descriptions of the people and situations of a small town likely culled from Capote’s childhood in Alabama. I spent my first afternoon back home at the Renaissance Fair revisiting moments from my childhood. Although I recognized almost no one, the types of people hadn’t changed. I called my mother that afternoon and we sat prettily in her lovely house, not talking at all about the troubles between us.

The next morning I read about how Dolly and Verena make their peace. I learned a little about family and what brings us together. I learned that they are not always the people we’d choose to be around, but that we are bound together nonetheless and how important that can be. I had a beautiful brunch with my mom and tried to be kind to her, even as we continued to not talk about our differences. She told me stories about her family and I listened. I told her what I’d been up to during all the months of silence. In her southern way, she talked around points to get at the heart of them and I realized this was familiar from Capote and that when things get really difficult, I write and speak this way too. When we said goodbye, she sobbed and sobbed and I drove helplessly away.

Capote and the City

My first morning back in Seattle, I read the story “Master Misery” which is about a young girl struggling to make it in the city who sells her dreams, literally, to an old man. It wasn’t an auspicious return, but, like most of the stories at the end of this book, is imaginative and metaphoric and wonderful to read.

You Said it’s a Slow Read?

Generally, “slow read” is a pejorative, but in Capote’s case, the book forced me to read slowly because every word was important. The sentences themselves were clean and simple, but there was a richness underneath them that I wanted to swallow whole and digest. So much for getting through a book.

“When was it that first I heard of the grass harp? Long before the autumn we lived in the China tree; an earlier autumn, then; and of course it was Dolly who told me, no one else would have known to call it that, a grass harp.”

That’s the first paragraph. You can see a little of what slowed me down, the inversion of the words “first” and “I” from how most of us would say it. The long, winding structure of the second sentence. But there is a richness there. I want desperately to know who is this Dolly with such wisdom. Is living in a China tree a metaphor? And what is the grass harp? TELLMENOW.

Capote subtly twists language in other ways that made me pay attention, and I loved him for it. Writing “brief case” instead of briefcase made me appreciate for the first time where the word came from. “Sunmotes lilted” was another phrase that made me swoon because the verb choice was so unusual and so perfect. But the phrase that made all the slow, close, attentive reading worth it was “Wind surpised, pealed the leaves, parted night clouds; showers of starlight were let loose.” I circled and underlined “pealed” and wondered how many copy editors had changed it to peeled, not understanding how this simple switch of vowels gave music to the language and the scene. It made me want to read the book all over again.

Coming Home to Capote the Writer

“I believe a story can be wrecked by a faulty line in a sentence.” – Capote

After falling so hard for The Grass Harp, I went back to Capote’s Paris Review interview. I’ve read all the interviews and have all the books (including when they were collected as Writers at Work), and Capote’s sticks has to be the one I underlined and annotated more than any other. Although it’s obvious from his writing how much control he has over his tools, I loved how his views on writing mirrored my own.

“Finding the right form for your story is simply to realize the most natural way of telling the story. The test of whether or not a writer has divined the natural shape of his story is just this: After reading it, can you imagine it differently, or does it silence your imagination and seem to you absolute and final?” – Capote

Few people would disagree that Capote is part of the literary canon, but I had forgotten how good he is. I remember In Cold Blood for the savageness of the murders rather than the writing, I remember Breakfast at Tiffany’s for Audrey Hepburn’s charming portrayal, and my vision of Capote the man is sparring with Dorothy Parker at some fabulous Manhattan cocktail party that I will never get to attend. But Capote was a writer and a damned good one. And despite the New York connections, he was from a small town like I am. The Grass Harp made me see appreciate him as a writer and appreciate where I come from. I scribbled down notes during and after the visit and I think someday soon that place where I came from will make it into my fiction or poetry.

My mom is having surgery this morning, again. It’s supposed to be routine, but none of her procedure ever has been. And yet all that spit and vinegar that makes her “not an easy woman” also must be part of the reason she’s alive after all of it and she will continue to live for a good long time. I am grateful for that. I am grateful that my grandmother gave me this book and guided me to read it when I did. I am grateful that Capote helped me find the voices of my own “grass harp, gathering, telling, a harp of voices remembering a story.”

If this review made you want to read the book, pick up a copy of The Grass Harp from Bookshop.org. Your purchase keeps indie booksellers in business and I receive a commission.

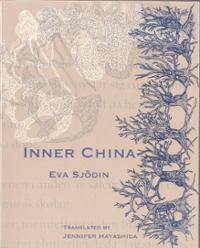

Frequent readers of this blog will know how much I appreciate spare language. Inner China by Eva Sjödin and translated from the Swedish by Jennifer Hayashida shows brilliantly just how much horror can be wrought with the sparest of language. The story of two small children who hide in the woods to escape sexual abuse is remarkably restrained. And therein lies the power of this poetry.

Frequent readers of this blog will know how much I appreciate spare language. Inner China by Eva Sjödin and translated from the Swedish by Jennifer Hayashida shows brilliantly just how much horror can be wrought with the sparest of language. The story of two small children who hide in the woods to escape sexual abuse is remarkably restrained. And therein lies the power of this poetry.